In our book, Discard Studies: wasting, systems, and power, Max Liborion and I write about defamiliarization and problem framing. in the context of the book we’re talking about how personal experience with garbage and waste tend to colour ‘the waste problem’ in a particular way. Very often those personal experiences with all the stinky, yucky stuff we put in bins are taken to be the waste problem as such. But, as we point out, that stuff we deal with as ‘waste’ personally is only a tiny portion of the overall amount of waste arising (as we also point out on the book, there is nuance to this: if you happen to be a waste manager at a mine site or manufacturing plant you’ve got a different personal experience with waste than me taking the trash for curbside pick up). ‘Only’ about 3 percent of all waste arising is municipal solid waste. The rest is industrial. There’s nuance in those numbers, sure, but the broader lesson holds. In my own early work on electronic waste (e-waste) I found it helpful to put some activist’s claims about e-waste dumping into perspective by comparing their data with reported data for waste arising from a single copper mine (more waste by far arises from a single copper smelter than from total e-waste exports from the US).

Defamiliarization is a technique that works by interrupting taken for granted assumptions about something (originally it was a literary technique). Comparing claims about total waste exports from the United States versus waste arising from a single copper smelter is an example of defamiliarization. It can be a useful way of testing assumptions and thinking about a problem framing. Problem framing is something that happens no matter what, but finding ways to think about problems differently helps to come at them from different analytical angles. Why? Because the way a problem is framed makes some solutions to it seem right and good while taking possible alternatives off the table or even making some alternatives unthinkable.

I recently came across some statistics about semiconductor end-markets that made me think about the importance of defamiliarization and problem framing again. Semiconductors are a kind of foundation or substrate on which anything with a chip in it, along with any and all software that runs on it, is based. Terms like ‘electronic’ and ‘digital’ have specific meanings for technical experts, but those terms are often used interchangeably outside of technical contexts. Similarly with ‘tech’ which is frequently used as a shorthand to talk about a whole sector of economic activity. All three of these terms – digital, electronic, tech – can be highly constrained or very loose categories, depending on how nerdy one wants to get.

Now, semiconductors are interesting to me because they are an obligatory passage point or pinchpoint for all of those categories, no matter how loosely or tightly defined. That makes semiconductors a very interesting aperture (to me anyway) from which to view the lives of electronics, however, narrowly or broadly one might define those technologies.

I initially came across data on semiconductor end-markets in a report on the use of PFAS (‘forever chemicals’) in semiconductor manufacturing (Jones and RINA Tech UK Limited (RINA), 2023, page 17). I followed the citation for the source of those data to another report about semiconductor supply chains done for the Biden Administration by the United States Department of Energy (United States Department of Energy, 2022, page 3). The latter report was a bit unsatisfying since the data were older and, frankly, some of the figures look like they were done by someone cutting and pasting by the seat of their pants. Eventually, I checked out what was available via Statista (my library has a subscription) and found quite a lot of data.

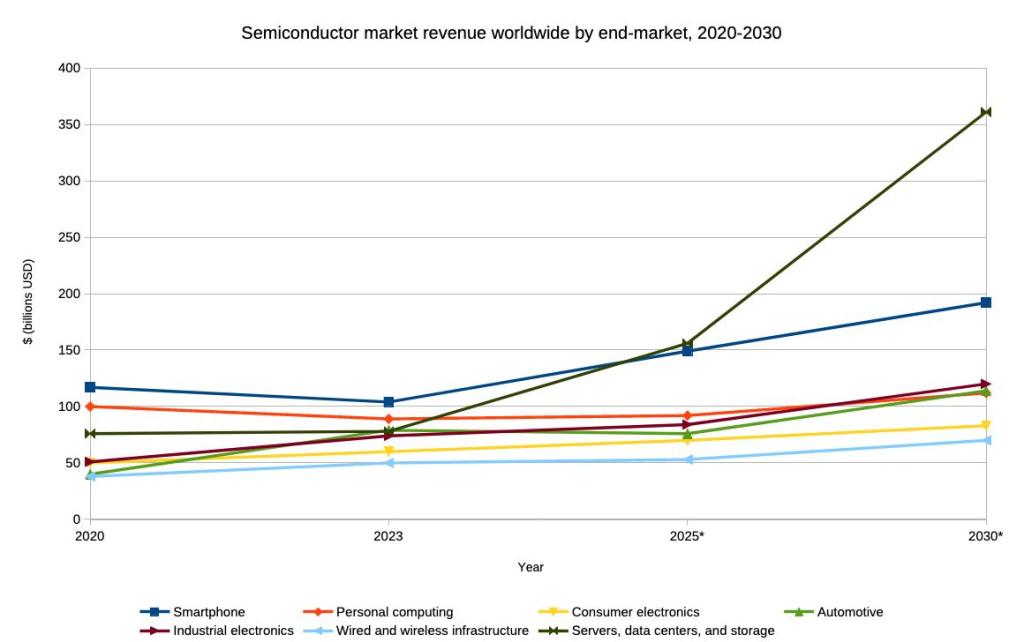

Ultimately, the Statista data for semiconductor end-markets are derived from annual reports of companies in the semiconductor manufacturing sector, such as ASML (ASML, 2024, page 39). All of these sources of data divide the semiconductor end-market into seven categories: (1) smartphone, (2) personal computing,(3) consumer electronics, (4) automotive, (5) industrial electronics, (6) wired and wireless infrastructure, and (7) servers, data centers, and storage. So these seven categories of end-markets are how a key player in the semiconductor manufacturing industry (ASML) presents the market at least to readers of its annual reports. I write that to make it clear that I am not imposing these seven categories onto the semiconductor industry. They are how the industry itself understands its market segments.

The data show some interesting patterns that drove home for me, once again, the importance of defamiliarization and problem framing. Although no semiconductor manufacturing industry insider will be surprised by the relative importance of each of the seven market segments, there may be some (at least somewhat) surprising patterns for those like me who are outsiders looking in on the industry.

Here are some interesting patterns in the data:

The rise of “servers, data centers, and storage” as the most valuable segment of the end market for semiconductors measured by billions of US dollars. With a start date of 2020 the data offer an important before and after snapshot of ‘artificial intelligence’ (on why I’m using single quotation marks here see for example: Bender et al., 2021; Bender and Hanna, 2025; Zitron, 2025). ChatGPT was released in November 2022. Since then the AI hype bubble has inflated a boom in data centre construction (see EpochAI for some useful overviews).

Back in the olden days of 2020 the server, data center, and storage and market for semiconductors was middle of the pack among the seven end-markets. The trend in this segment enters the ‘number-go-up’ phase by 2023 and the ‘number-really-go-up’ phase after 2025. If Statista’s numbers hold, the server, data center, and storage sector will comprise about 34% of the end-market for semiconductors in dollar terms by 2030, having more than doubled in value since 2020 when the segment accounted for about 16% of semiconductor end-markets.

Over the same 2020-2030 time period, a clutch of end-market categories (smartphone, personal computing, and consumer electronics) are projected to decline in prominence from about 57% of total market value in 2020 to less than 37% by 2030. The automotive end-market will have more than tripled in dollar value by 2030, shifting from about $40 billion (about 8% of the end-market) in 2020 to about $114 billion (about 11% of the end-market) by 2030. Cars and buses will increasingly become computers we sit in.

What might all this mean? There are a lot of different ways one could go to answer that question (I admit it’s an overly broad and poorly specified question). Here I just want make the following small point: similar to why it is important to defamiliarize problems of waste, so too is it important to defamiliarize what might be taken for granted as the ‘tech sector’. Consumer electronics often stand-in for the sector as a whole in media, NGO, and scholarly research stories about that sector, but the emerging trends across the sector point to the diminishing importance of the consumer electronics segment relative to other segments of semiconductor end-markets. There is nothing inherently wrong with the stand-in role consumer electronics play in commentary, criticism, and research about the tech sector, but it is important not to mistake a part for a whole.

Thinking about the ecological problems arising from the mining for and manufacturing of electronics as if consumer electronics represent the whole sector is likely to lead to misspecifications of those problems and of alternatives that might be offered to mitigate or eliminate them.

Works Cited

ASML. Annual Report 2024. 2024. https://ourbrand.asml.com/m/79d325b168e0fd7e/original/2024-Annual-Report-based-on-US-GAAP.pdf.

Bender, Emily M., Timnit Gebru, Angelina McMillan-Major, and Shmargaret Shmitchell. “On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots: Can Language Models Be Too Big? 🦜.” Proceedings of the 2021 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency (New York, NY, USA), FAccT ’21, March 1, 2021, 610–23. https://doi.org/10.1145/3442188.3445922.

Bender, Emily M., and Alex Hanna. The AI Con: How to Fight Big Tech’s Hype and Create the Future We Want. First edition. Harper, 2025.

Jones, Emily Tyrwhitt and RINA Tech UK Limited (RINA). The Impact of a Potential PFAS Restriction on the Semiconductor Sector. Nos. 2022-0737 Rev. 0. SIA PFAS Consortium, 2023.

Statista. “Semiconductor Market Revenue Worldwide from 2020 to 2030, by End Market (in Billion U.S. Dollars).” November 19, 2025.

United States Department of Energy. Semiconductor Supply Chain Deep Dive Assessment. 2022. https://www.energy.gov/sites/default/files/2022-02/Semiconductor%20Supply%20Chain%20Report%20-%20Final.pdf.

Zitron, Ed. “The Hater’s Guide To The AI Bubble.” Ed Zitron’s Where’s Your Ed At, July 21, 2025. https://www.wheresyoured.at/the-haters-gui/.

You must be logged in to post a comment.