Is it possible to design a structure of government which will be stable and predictable? Hopefully, of course, stably and predictably benign? History affords no evidence of it. But history affords no evidence of semiconductors, either. There is always room for something new.” (Moldbug (aka Curtis Yarvin), 2008, p. 21)

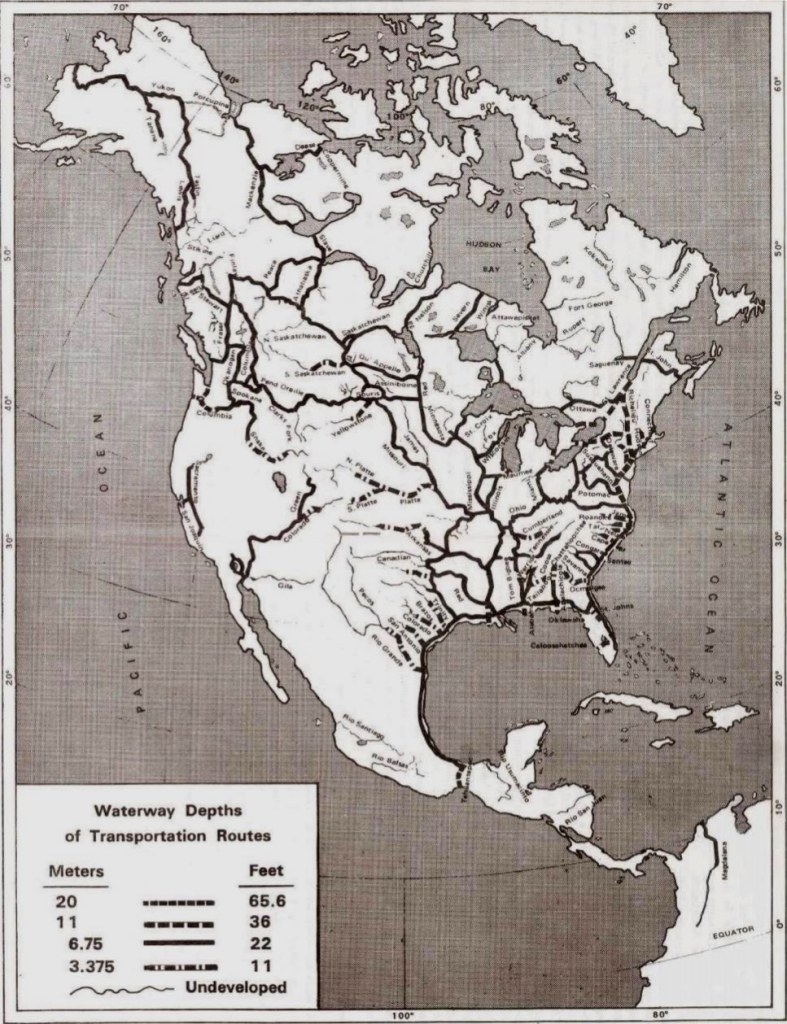

In a piece for CBC, reporter Geoff Leo offers a biographical sketch of Elon Musk’s grandfather Joshua Haldeman and his political links to Canada. I had known about the links between Haldeman, Musk, and a social movement called technocracy from other sources, but what caught my eye was a map that appears in Leo’s piece with the title “Technate of America”.

This essay is an attempt to map out, however incompletely, the geographical imaginaries of a political coalition sometimes dubbed the ‘tech right’. What does it look like? Of whom and of what is it composed? Where? When? And under what conditions? I started wondering about these questions while reading Leo’s article on Musk’s grandfather. The Technate of America map struck me because in all of the news taking place in the context of an ongoing coup in the United States, President Trump was openly musing about taking control of Greenland, Canada, and the Panama Canal.

Even now Trump’s pronouncements are still being reported in diametrically opposed ways: either scoffed at as supposedly kooky outbursts of an unhinged US President, but also as genuinely grave threats to sovereignty. Seeing the ‘Technate of America’ map suddenly brought a certain kind of logical coherence to the otherwise seemingly chaotic pronouncements from the White House. The map in Leo’s piece were what are today Canada and Greenland both imagined as part of the same geographical unit: the Technate of America. Suddenly, two places that few people would have lumped into the same bucket of meaning were being depicted as if they logically belonged together. Now some newsy buckets that were all sloshing around as more or less separate puddles of worry for me started to cohere into a more understandable picture.

There’s a term human geographers use when they’re talking about peoples’ taken for granted notions of how the space of the world is ordered: a geographical imaginary. By “imaginary”, geographers aren’t suggesting that peoples’ ideas of how the world is bordered and ordered are just made up (in the sense of being fake) but are, instead, ‘constructed’ or ‘built’. No one would mistake describing a house as having been constructed or built as also a claim that the house is made up or fake, even if it was imagined by an architect or developer at some point. A house can take on all sorts of different shapes and sizes and be made in all sorts of different ways with all sorts of different materials and built by a collection of a whole bunch of people. Yet, no one would mistake someone describing that house as being ‘made’, ‘built’, or constructed’ for also being a claim that the house is ‘fake’ or ‘made up’. Geographical imaginaries are like this too. They have some correspondence with some actual states of affairs, but they bring with them ideas about those states of affairs e.g., stated and unstated presuppositions and value judgements about who or what belongs where, when, and under what conditions. Geographical imaginaries, then, “are vitally implicated in a material, sensuous process of ‘worlding’ “ (Gregory, 2009). ‘Worlding’ is another way of describing how we all individually and collectively have taken for granted assumptions about the world as an ordered whole. Some people act as if a collection of not necessarily like things, such as Canadians and Greenlanders, nevertheless all cohere together into some common world (the ‘as if’ part of this is important, since a geographical imaginary may or may not fully lineup with how the world actually is).

I started to wonder about how this map of the Technate of America might or might not mesh with other geographical imaginaries in play amongst the people and organizations associated with Musk’s technocracy lineage and operating in his orbit. There’s DOGE, of course, but also two people in this milieu who have published treatises specifically advocating for remaking the political geographies of today into new forms. One of these people is Balaji Srinivasan, who advocates for what he calls the network state. The other is Curtis Yarvin, who argues for what he calls the patchwork (Moldbug (aka Curtis Yarvin), 2008).

A Folksonomy of the tech right

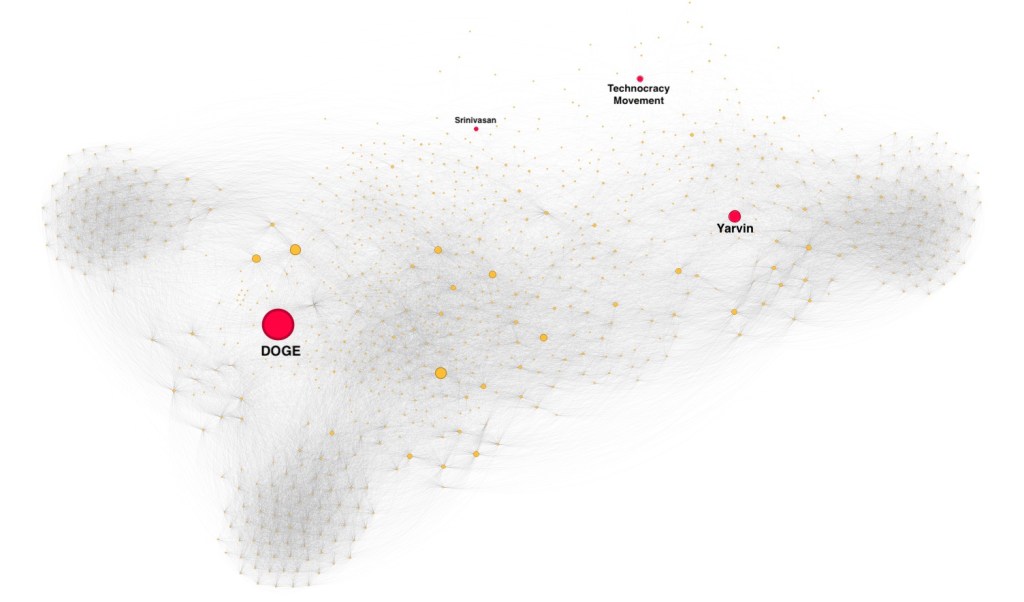

There are a few ways into this question of the tech right’s geographical imaginations. One way is to use a free tool for tracing the links between Wikipedia pages as a form of folksonomy–a term attributed to Thomas Vander Wal to describe classification systems created by people who may or may not be professionally trained information taxonomists. A folksonomy can be thought of as a classification system emerging from a bunch of people other than me, the researcher who is interested in the meanings people are attributing to a given concept or concepts. The tool I used is called Seealsology, developed by the Density Design Lab at the Politecnico di Milano.

Seealsology is designed to help researchers quickly explore the “semantic area related to any Wikipedia Page”. Basically, the software allows a researcher to harvest links to, from, within, and between any given Wikipedia page or pages. After harvesting, the software outputs a graph, or in geographical terms, a topological map, linking nodes comprised of all the harvested links into an overall network of meaning derived from the initial Wikipedia pages the search started from.

I used Seealsology to harvest the links from the following Wikipedia pages:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Department_of_Government_Efficiency

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Balaji_Srinivasan

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Curtis_Yarvin

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Technocracy_movement

The approach I took gave me a social graph of the meaning space in which editors of Wikipedia place DOGE, Srinivasan, Yarvin, and the technocracy movement. This approach meant that each of the Wikipedia pages above were crawled for all hyperlinks appearing on them. What results is a network of nodes and links (edges, in network analysis parlance) that makes it easy to show which nodes, if any, the four Wikipedia pages share with one another. Shared nodes can be enlightning because they show who or what forms the connections or bridges of a given semantic space. Let’s have a look:

In the figure above, the four Wikipedia pages that seeded the analysis are shown in red. Links found on those pages are represented by nodes in yellow. Connections between nodes are all those wispy grey lines.

If you want to play around with an interactive version of the network above, I built a little website for that. Try looking up your favourite person in the search bar on the site, say, Marc Andreessen or Elon Musk and see who or what they’re connected to.

In this case, the size of all of the nodes are ranked by their ‘betweeness centrality’. Betweeness centrality is a technical term in graph analysis. In plain language it is a measure of the shortest path from all nodes to all other nodes on the graph. In other words, betweeness centrality traces the fewest number of ‘hops’ a hypothetical traveller of the graph could take to get from one node to all other nodes in the network. Each time a given node is landed on it gets counted. Those nodes with the highest counts (i.e., highest betweeness centrality) are the nodes that offer the shortest path from any given node to all other nodes in the network. Betweeness centrality is a way of thinking about the relative importance of a given node in a network. The assumption is those nodes with the highest betweeness centrality are more important than those with lower betweeness centrality.

Of the four Wikipedia pages used to seed the graph in the figure above, the page for DOGE has the highest betweeness centrality followed by Yarvin, Srinivasan, and the technocracy movement. This arrangement suggests the relative importance of each of the seed pages to the semantic space depicted in the graph. The DOGE node is most frequently the shortest distance to all other nodes in the network from any given starting point, followed by the nodes for Yarvin, technocracy, and Srinivasan respectively.

Phew.

Besides betweeness centrality, it can also be enlightening to focus on the nodes that link the various clusters. We see some people we might expect acting as bridges between Yarvin and DOGE e.g., Donald Trump, Peter Thiel, Marc Andreessen, and Javier ‘Chainsaw’ Millei (again, if you’re curious you can look them up here).

A perhaps less well known name linking the nodes for Yarvin and for DOGE is Jared Taylor. Taylor founded a think tank called the New Century Foundation (NCF) and edited its flagship publication ‘American Renaissance’. Taylor, the NCF, and American Renaissance have been described as “white nationalist”, “white supremacist”, and sponsors of conferences “where racist ‘intellectuals’ rub shoulders with Klansmen, neo-Nazis and other white supremacists”(Southern Poverty Law Center, a; Southern Poverty Law Center, b; Tilove, 2006). To be clear, such a link is only evidence of connection made in the semantic space forged by the many editors of Wikipedia articles. The specific connection to Yarvin arises from his blog that references Taylor while arguing that he, Yarvin, is himself simultaneously not a white nationalist while also being, “not exactly allergic to the stuff”. Meanwhile, Taylor’s connection to DOGE arises from Noah Peters, apparently a member of the DOGE team who has also ostensibly acted as Taylor’s lawyer.

What the above suggests are that there are meaningful linkages between the four Wikipedia pages that seeded the graph: Yarvin, Srinivasan, DOGE, and the technocracy movement. Further the network has a structure in which Yarvin is an important link between all of their nodes. Meanwhile, specific actors act as bridges between the different geographical imaginaries each of these interests represent. This network can be thought of as forming a core set of co–linkages between different archipelagos of interest of the broader tech right.

The archipelagos (or clusters) represent Wikipedia links about people places and things associated with the four Seealsology seed pages. Zooming into each cluster helps us better understand the semantic space. The DOGE cluster is closely associated with, for example, Musk and his companies such as Twitter, x.com, PayPal, Starlink, and Tesla among others. Other nodes in the cluster include members of Musk’s family, such as his mother and father as well as several of his children. There are also links to political action committees (PACs) funded by Musk (e.g., America PAC) and a variety of issues Musk or his companies are entangled with (e.g., the Tesla Takedown protests, the handling of union activity at Tesla).

One of the valuable aspects of creating this kind of network map using Seealsology is how it can surface people, places, or things that may be of interest to a researcher yet otherwise less immediately on one’s radar. Just as an example, some thing that caught my eye in the Musk cluster is a reference to “Astra Nova School”, something associated with Musk I had never heard of. It turns out to be an iteration of a private school Musk started for his own children and then sold off as a standalone enterprise.

The DOGE cluster represents a grab bag of topics associated with its actions. Topics include, for example, the hiring freeze of federal employees, the mass firing of federal employees, specific executive orders, but also a variety of counter political moves emerging since the coup began. There are, for example, links to the 50501 movement, as well as a variety of other protest movements e.g., protests against mass deportation, Stand Up for Science, and Canadian boycotts of the US. These links and others like them are important findings from this scoping of the semantic space of the US tech right. They clearly indicate that cracks of resistance are opening up, that although the tech right and the broader far right may appear powerful – and they are in some respects – they are not monolithic. Even in the face of overwhelming odds people are already organizing to resist. What’s more important is that, as much as there are alignments between interests with enormous wealth and power, there also are other cracks within the coalition of the right that this semantic space can help identify. Such cracks are exploitable. Other cracks exist, too, as we’ll see.

The Yarvin cluster is comprised of an admixture of political theories and theorists, those mostly associated with various flavours of libertarianism. The cluster includes ideas that those outside of certain very niche political theory graduate seminars (or corners of the reactionary and self-aggrandizing ‘Dark Enlightenment’ blogosphere) might find alternately baffling and hilarious. But this is probably a good place to remember Cory Doctorow’s take on Milton Friedman–whose son David is among the nodes in the Yarvin cluster and who has contributed much of his father’s thinking to the geographical imaginaries in play. The elder Friedman wrote in a preface to the 1982 edition of his book Capitalism and Freedom:

Only a crisis actual or perceived produces real change. When that crisis occurs, the actions that are taken depend on the ideas that are lying around. That, I believe, is our basic function: to develop alternatives to existing policies, to keep them alive and available until the politically impossible becomes politically inevitable (Friedman, 1982, p. 7).

I think it’s accurate to describe the events unfolding vis-à-vis the Trump administration as a crisis, actual or perceived (it’s hard to be wrong with such a description). Given that, it might be wise to map out the position of one’s enemies, real or perceived. They are after all already doing that to those of us who do not fit into their geographical imaginaries.

Geographical Imaginaries of the Tech Right

The Yarvin cluster includes what, in my view, are some genuinely odious ideas. I say that because the logical conclusion of some of those ideas includes the eradication of various groups of people of which by circumstance or choice my friends, my family, and myself would be among. Perhaps you think I’m being a catastrophist, but here is Yarvin in his own words as he answers the question of what to do with anyone deemed undesirable to the social ordering he desires (that is, “…adults who are not productive members of society [those] not capable of earning a living, [those] not accepted […] and [those] not wanted by any other” (Moldbug (aka Curtis Yarvin), 2008, p. 28)):

…what should you do with these people? I think the answer is clear: alternative energy. Since wards are liabilities, there is no business case for retaining them in their present, ambulatory form. Therefore, the most profitable disposition for this dubious form of capital is to convert them into biodiesel, which can help power the Muni buses.

Okay, just kidding. This is the sort of naive Randian thinking which appeals instantly to a geek like me, but of course has nothing to do with real life (Moldbug (aka Curtis Yarvin), 2008, p. 28).

Mhm. Yes, just kidding. It’s only a joke, you see. Can’t we even joke anymore? Indeed.

So what isn’t Yarvin kidding about? “Our goal, in short, is a humane alternative to genocide. That is: the ideal solution achieves the same result as mass murder (the removal of undesirable elements from society), but without any of the moral stigma” (Moldbug (aka Curtis Yarvin), 2008, page 28; italics in the original text).

As we say in discard studies, know a system by what it discards, how, and under what conditions.

Instead of mass murder, Yarvin merely proposes to do what, exactly? Not to “liquidate” those deemed undesirable (Oh! Mass murder–how indecorous–clutch my pearls—No, no, not that…). What’s the “best humane alternative to genocide” of undesirables? Why, “to vitualize them”, of course (Moldbug (aka Curtis Yarvin), 2008, page 29; italics in the original text). Yarvin is serious, apparently:

A virtualized human is in permanent solitary confinement, waxed like a bee larva into a cell which is sealed except for emergencies. This would drive him insane, except that the cell contains an immersive virtual reality interface which allows him to experience a rich, fulfilling life in a completely imaginary world.

The virtual worlds of today are already exciting enough to distract many away from their real lives. They will only get better. Nor is productive employment precluded in this scenario—for example, wards can perform manual labor through telepresence. As members of society, however, they might as well not exist. And because cells are sealed and need no guards, virtualization should be much cheaper than present day imprisonment. I like virtualization because it can be made to scale (Moldbug (aka Curtis Yarvin), 2008, p. 29)

Yarvin is explicitly drawing on The Matrix. But instead of siding with its (retrospective) trans allegory of resisting an eliminationist regime of machines, he sides with the machines.

Yarvin advocates for a geography of polities he calls ‘patchwork’: “…we can think of Patchwork as a new operating system for the world” (Moldbug (aka Curtis Yarvin), 2008, p. 4). It is, “…any network consisting of a large number of small but independent states. To be precise, each state’s real estate is its patch; the sovereign corporate owner, i.e., government, of the patch is its realm. At least initially, each realm holds one and only one patch. In practice this may change with time, but the realm–patch structure is at least designed to be stable.” (Moldbug (aka Curtis Yarvin), 2008, p. 4). But Yarvin is keen to not have the patchwork descend into feudalism. Therefore patchwork needs, “a strong security design” (Moldbug (aka Curtis Yarvin), 2008, p. 4). More on that momentarily. But, the fundamental issue, according to Yarvin, is a systems engineering problem (indeed, he describes the crafters of the US Constitution as “political engineers”, and on that point he’s not wrong (Latour, 1993; Latour, 2005)).

As a self-described “reactionary”, Yarvin claims for himself the right, “to borrow freely across time as well as space, incorporating political designs and experience from wherever and whenever.” (Moldbug (aka Curtis Yarvin), 2008, p. 5). So any criticism of patchwork shouldn’t bother with charges of incoherence since even if found, it doesn’t count against it. Discard studies argues that to subsist and persist, any system must discard. Paying attention to the people, places, and things that are so discarded can help assess a system’s ethics, operations, and values. Coherence (among much else) is discarded from Yarvin’s patchwork. So: know a system by what it discards. Even a good faith debater needs to recognize what an enemy is going to even recognize as legitimate criticism or not.

Patches in a patchwork are businesses, literal corporations. Yarvin is advocating literally for a real estate play in which a CEO reigns supreme, with the caveat that such reign is limited by the degree to which a CEO is able to satisfy the customer service demands of a patch’s residents (and, of course, raises the question of whose land a patch comprises). The sovereign power of a patch “profit by taxing all economic activities within a patch” (Moldbug (aka Curtis Yarvin), 2008, page 9). This is a bit of a tell about Yarvin’s theory of sovereignty and the state. Latent in it is the idea that state’s fund themselves by taxing their populace. While this is a common understanding about how the state works, there is a whole body of literature premised on available archaeological, ethnographic, and historical evidence that suggests otherwise (Graeber, 2011). For example, modern monetary theorists or (‘neo-Chartalists’) argue that states tax for two primary reason (MMT Podcast, 2025):

- to create a demand for the currency they issue (so that the state, as the issuer, can spend that currency into circulation and provision itself by buying goods and services on offer in exchange for its currency that everyone else must pay taxes with) (Berkeley et al., 2024; Kates, 2025).

- to remove from circulation some of the currency the state issued earlier so that everyone’s spending (including the state’s) remains within the real productive capacity of the economy (this reduces the chance of too much inflation).

A given currency issuing state may tax for other reasons as well, but what those taxes have absolutely nothing to do with is funding the state that issues the currency that everyone pays their taxes in. This is important to understand, because at the base of the ability to collect taxes is the ability to exact violence against those unwilling or unable to pay. Reactionaries like Yarvin might decry taxes as themselves a form of theft and violence as such, but violence does not distinguishes contemporary currency issuing states from Yarvin’s preferred system of a patchwork. How so?

Patches are to be “administered” (Yarvin seems allergic to any word whose stem includes ‘govern’) as a corporation. Not like a corporation, but as a corporation. In such an arrangement there is a chief executive, “whose decisions are final” (Moldbug (aka Curtis Yarvin), 2008, p. 9). Almost parroting the cliche libertarian joke about how many libertarians it takes to screw in a lightbulb (Answer: none. The market would’ve solved the problem already), Yarvin argues that if there were a better organizational structure than a joint stock company for maximizing efficiency it would have been found already. “Someone would have found a way to construct a firm on this design, and it would have outcompeted the rest of the stodgy old world” (Moldbug (aka Curtis Yarvin), 2008, p. 9). Grasping for historical analogues, Yarvin points to chartered companies, though argues they are at best an approximation of what he has in mind. His preference is a joint stock company premised on natural/divine right monarchy, as argued by the 15th century English political theorist Sir Robert Filmer (see Moldbug (aka Curtis Yarvin), 2008, page 10). For real.

In Yarvin’s analysis, Filmer’s justification of natural/divine right of kings comes down to this: the status quo is the status quo because it is the status quo. Stable social organization, you see, “is a Schelling point of nonviolent agreement” (Moldbug (aka Curtis Yarvin), 2008, p. 11). Do not ask why things are the way they are. Do not suggest they ought to be changed. Yarvin is apparently serious in arguing that, for example, though the rule of the House of Bourbon is arbitrary, its rule represents a stable equilibrium point arising from the default choices of people and is therefore ‘nonviolent’. You can almost hear the joke: How many libertarians does it take to solve a social problem? Answer: None. There can be no social problems because the market will have solved them already.

But what if anything mitigates the tyranny of the CEO of a patch? Answer: the profit motive arising from a bilateral contract between a patch (read joint-stock company) and its residents. The contract promises that residents will be treated fairly and, should they not like the conditions of the patch they are in, they may decamp with all of their assets to any other patch that will have them (Here, again, we bump into what Yarvin simply asserts as true: actual sovereign realms, such as a state, make their “take” from taxation (Moldbug (aka Curtis Yarvin), 2008, p. 15)–a point disputed by others, such as the Chartalists).

In the patchwork, security is absolute, guaranteed with total surveillance of residents and the CEO’s “robot armies” (Moldbug (aka Curtis Yarvin), 2008, page 33). The situation inside a given patch is either totally secure or not at all secure (and, if the latter, then it is not a patch).

In the orbit of the semantic space surrounding Yarvin we can find a grab bag of libertarian economists, moral philosophers, and outright racists. This is a cluster of ideas and people with little coherence to unite them other than various ways of interpreting American libertarianism. Not all of them are eliminationist and racist, but some of them are. And, these are–pace Friedman–alternatives being kept alive, available, and possibly no longer impossible as real events of the ongoing coup unfold.

Silicon Valley’s Ultimate Exit: the network state

Srinivasan’s network state is premised on the assumption that it is possible to do something like Yarvin’s patch, but “digital first”. Here’s Srinivasan offering his recipe for how to “to start a new country” (Srinivasan, p. 13):

Our idea is to proceed cloud first, land last. Rather than starting with the physical territory, we start with the digital community. We create a startup society, organize it into a network union, crowdfund the physical nodes of a network archipelago, and — in the fullness of time — eventually negotiate for diplomatic recognition to become a true network state. We build the embryonic state as an open-source project, we organize our internal economy around remote work, we cultivate in-person levels of civility, we simulate architecture in VR, and we create art and literature that reflects our values.

When we crowdfund territory in the real world, it’s not necessarily contiguous territory. Because an under-appreciated fact is that the internet allows us to network enclaves. Put another way, a network archipelago need not acquire all its territory in one place at one time. It can connect a thousand apartments, a hundred houses, and a dozen cul-de-sacs in different cities into a new kind of fractal polity with its capital in the cloud” (Srinivasan, p. 14).

In this context, ‘digital first’ is a bit like expressing a preference for water that is fluid first and H2O second. I mean, sure, you can express that preference of priority, but does it make any meaningful sense?

‘Digital first’ is a continuation of a common but mistaken way of representing digital technologies, including the Internet. Back in the olden days of the early 1990s as the Internet was being commercialized there was a great deal of fizzy talk about a borderless world and the end of geography. These kind of ideas continue in the present day, even though it should be obvious that, like the H2O of water, no digital technology can exit its needs for human and nonhuman materials and labour to subsist and persist.

Srinivasan claims that in a network state “there is this entire digital world up here which we can jack our brains into and we can opt out”. Network states have all the terra incognita and terra nullis needed. He writes:

Terra incognita returns. The network state system assumes many pieces of the internet will become invisible to other subnetworks. In particular, small network states may adopt invisibility as a strategy; you can’t hit what you can’t see.

Terra nullius returns. The network state system further assumes that unclaimed digital territory always exists in the form of new domain names, crypto usernames, plots of land in the metaverse, social media handles, and accounts on new services (Srinivasan, p. 230).

Both these assumptions of the network state system presuppose that the infrastructure on which these networks run require no actual geography.

Readers already familiar with the substantial research literature in studies of Indigenous sovereignties and settler colonialism will, no doubt, have already noted whole hinterlands of unstated assumptions baked into Srinivasan’s assumptions of terra incognita and terra nullis (if you’re not already familiar with those ideas, here is a very brief way into them). Srinivasan puts substantial faith in freedom of contract, for example. Yet, the Network State only imagines Indigenous peoples in what is now North America as just so many polities in Hobbesian wars of all against all. “We can infer this”, claims Srinivasan, because the Mongols invaded Europe and because an archived webpage of the Canadian Government called “Warfare in Pre-Columbian North America” says so (Srinivasan, p. 94).

Regardless of the question of the accuracy of these inferences, it is clear that the network state only imagines Indigenous peoples to be polities of the past. There is no sense at all that not only do indigenous peoples persist, but in multiple cases do so with active contracts i.e., treaties with other sovereignties. Large portions of what is today Canada, for example, are treaty lands. These treaties are not some exotic bygone arrangement of ancient history, but actual contracts with legal meaning (which is not to suggest that the settler-colonial parties to these contracts have lived up to their obligations under them). If network statists believe in the morality and enforeceability of contracts, then they believe the same about the contracts of treaties — or they dismiss them, which throws into question their sincerity about contracts altogether.

Moreover, absent the land from which minerals are mined, the chemicals synthesized, the water appropriated, and the semiconductors etched, there is no digital. The digital is never, and cannot ever be, unearthly. It should not be possible to presuppose otherwise, and yet, apparently it needs to be pointed out again (and again, again, and again…). Even a narrow and superficial focus on Silicon Valley shows this to be the case. Concerns about pollution arising from electronics manufacturing in Silicon Valley go back to the 1970s (Bernstein et al., 1977; Siegel, 1982; Smith et al., 2003). Well documented harms to electronics manufacturing labourers in the region go back to the early 1980s (LaDou, 1986, 1984). The inextricable entanglement of the electronic sector in the Valley with the US Department of Defense and the broader military-industrial complex has its roots back to at least 1930s (Lécuyer, 2007; Scott and Angel, 1987).

Since reform is impossible, Srinivasan argues, the only solution is ‘exit’ (citing Albert O. Hirschman, Voice, Exit and Loyalty). During a talk at Y-Combinator in 2013 Srinivasan notes that his father emigrated from India to the US because there was no way he would be able to vote to change the system in which he lived (the reference to Exit, Voice, and Loyalty does not contemplate any but these three possibilities, even in the face of actual historical events that don’t match them i.e., that provide other alternatives; a critique of Hirschman’s work is beyond what I’m doing in this post, so suffice it to say that in my view, a typology is insufficiently nuanced if it categorizes, say, the French revolution, the Haitian revolution, the Sparticist uprising, and January 6th as all expressions of ‘voice’, just really shout-y ones, without being able to distinguish between the morals and values at play in each).

Srinivasan argues that exit is about alternatives (which is a good reminder that alternatives analysis does not automatically lead to universal goods or a good that can be taken as universal). The need for an alternative arises because in Srinivasan’s analysis there is a a clash of civilizations between Silicon Valley and what he describes as old centres of power such as Boston for higher education (e.g. Harvard), New York (media and finance e.g., Madison Avenue, book publishing, and Wall Street), Los Angeles (also media aka Hollywood), but especially Washington DC (which is a stand-in for unwanted government regulation of any kind). His argument circa 2013 is that in the previous 20 years the “digital world” of Silicon Valley became a competitor to all these “paper belt” old centres of power “by accident”.

Exit is a reaction to feeling dissed by the establishment, a premise that presupposes that Silicon Valley never was part of it. This is a premise that takes a great deal of historical blindness to take seriously (see Harris, 2023 for a key source of evidence; even if one differs in the interpretation of the meaning of that evidence, the idea that Silicon Valley’s power is distinct from the power of ‘Washington’ and merely a random accident is not sustainable).

The Technocracy Movement and the Technate of America

The Technocracy Movement has its roots in the early post-World War I years of the 20th century. It is often attributed to the efforts of Howard Scott, who styled himself an engineer (though he may not have had formal training as such). Scott managed to assemble a collection of experts designating themselves the Technical Alliance and dedicated to documenting the wastefulness of what they called the Price System. The latter system wasn’t inherently capitalist. In a 1945 publication the Alliance’s successor, Technocracy Inc (still involving Scott), described the Price System as “any social system whatsoever that effects its distribution of goods and services by means of a system of trade or commerce based on commodity valuation and employing any form of debt tokens, or money, constitutes a Price System” (Technocracy Inc., 1945, page 126 italics in the original text).

Technocracy claimed not so much to be non-political or apolitical, but outside politics altogether, operating in the realm of objective Science (capital ‘S’). The movement has been variously criticized as a form of either left or right totalitarianism, even as its founder, Howard Scott, claimed that “[t]echnocracy is opposed to the institution on this Continent of any form of fascism, nazism, communism, or tory democracy” (Scott, 1939, page 7). Indeed, some of the movements own advocates explicitly claimed technocracy to be anti-fascist (e.g., Ivie, 1957).

Mid-20th century technocracy was a capacious container of ideas. Here is Elon Musk’s Canadian maternal grandfather, Joshua Haldeman, in the July 1940 edition of Technocracy Digest:

No other Country has anything that the North American people either want or require. Here on this Continent we have everything that is needed to provide us with certainty and security … we don’t need the Price System … the application of Science to the Social Order would automatically free us from these nauseating encumbrances (Haldeman, 1940, page 6).

What encumbrances, you might ask? Haldeman offers a litany including:

…taxes, tariffs, contractual obligations, litigations, legislations, federations, acts, constitutions, property rights, money, debt or debentures; we don’t need banks, bandits, or bastards […] fear, insecurity, uncertainty and want; we don’t need poverty, politics or polygamy [and] we don’t need churchianity (sic) displacing Christianity” (Haldeman, 1940, page 6).

Clearly, mid-century technocracy contained multitudes.

In contrast to Yarvin who wants patches run by CEOs of joint stock corporations and in contrast to the ‘digital first’ network state favoured by Srinivasan, technocracy’s original thinkers were continentalists with a grand faith in scientists and engineers to substitute, “political maneuvering and partisan interests” for “empirical management of resources and production” (“About Technocracy – Technocracy Inc. – Official Site”). Technocracy’s orientation to politics is part of a substantial current of thought amongst some engineers and technologists who claim politics as usual can be dispensed with (Finley, 2015). In its place is a faith in governance by ostensibly apolitical quantitative and technological means:

Technocracy finds that the production and distribution of an abundance of physical wealth on a Continental scale for the use of all Continental citizens can only be accomplished by a Continental technological control — a governance of function — a Technate (Hubbert, 1945, page vii).

Technocracy Inc., mapped that Technate as a continental object (as in the map above) fully accessible to their vision of re-engineering.

The current POTUS mused about Canada as a “very large faucet” on the campaign trail (Dryden, 2025). What might’ve seemed a bizarre raving actually has real referents. The maps of the Technate at least have the benefit of converting the current US administration’s claims about buying Greenland and annexing Canada from seemingly random outbursts of one man’s ego into a geographical imagination with a certain degree of coherence (if it needs saying, I’m just describing, not endorsing, that geographical imagination). Archivists at the University of Alberta describe how the Technocracy Movement became, “relatively insignificant” post-WWII, but nevertheless “the movement has continued on into the early years of the 21st century” (“Technocracy fonds – Discover Archives”; those archives have been scanned and are available at the Internet Archive).

Technocracy’s proponents were writing about control of water at a continental scale in the Technate in the early 1930s (Scott, 1936). A 1947 issue of The Northwest Technocrat reproduced a Technocracy Inc map of “Continental Hydrology” (Bounds, 1947). A very large faucet, indeed.

Readers might see a strong resemblance to a seemingly similar proposed continental megaproject called the North American Water and Power Alliance (NAWAPA) (for more on NAWAPA, see for example Gleick et al., 2014 on ‘zombie’ water projects and Reisner’s 1993 classic, ‘Cadillac Desert’). Notwithstanding the physical resemblance, however, Technocracy’s founder, Howard Scott, was highly critical of the private industry orientation of NAWAPA. In a scathing retort to one of Technocracy’s Canadian advocates Scott notes receiving their pamphlet on NAWAPA and then proceeds to quote from Lewis Caroll’s ‘The Walrus and the Carpenter’. Of the engineering firm most associated with promoting NAWAPA, the Ralph M. Parsons Co., Scott sniffs that the firm, “undoubtedly had the best publicity and advertising men compose and write their folder, but […] they are new to the problems of a Continent”, they “are motivated by the vistas of huge pecuniary projects with water as a commodity”, and “hypnotized by the profitable potential” (Scott, 1969, page 30 of 72). Technocracy’s plan for ‘Continental Hydrology’ was to be outside any project premised on the Price System. NAWAPA was anathema.

Technocracy’s multitudes leave us in interesting territory. It was a movement that saw the end of the price system as one of its core values and, in its own way, understood itself as a movement outside of politics. In place of grubby politics, technocracy sought to institute what its advocates understood to be the universality of Science (capital ‘S’) for objective decision making. The dream was and remains non-political, automatic decision making flowing from solutions that are always purely technical. Technocracy’s advocates persist in this approach in their writings online.

In early 2001 the website for Technocracy Inc. showed what the movement understood as the differences between political decision-making versus nonpolitical, technological solutions that work “automatically”. They used a version of the infamous trolley problem to do it. Instead of politics (decrees, edicts) technocrats want technological solutions that work “automatically”. Sometimes that approach can work, but not always and everywhere. The technocrats might not like what they deem to be politics in the form of politicians issuing decrees and edicts, but commands, judgements, regulations, etc. are, nevertheless, inevitably scripted into any quantitative formula or technical device.

Whats more, the movement might profess to be anti-fascist, anti-Nazi, anti-communist, and anti-totalitarian, but it isn’t anti-colonial. In presupposing access to the continent of North America for its own goals, technocracy smuggles in a false universalism. Meanwhile, the movement’s website has been refreshed suggesting that the ideas of technocracy that were lying around might, indeed, be becoming politically possible again.

Srinivasan’s exit to the network state gestures at similar non-politics of technocracy even while simultaneously remaining thoroughly within what technocracy would view as a capitalist price system. The network state is no power grab in that formulation, it’s just an opt-out form or so Srinivasan’s claims go.

Right now Srinivasan is running network school. This is both an educational project and capital accumulation initiative to demonstrate ”provable demand” for land. Here, Srinivasan explicitly points to Elon Musk’s approach to building Model 3 Tesla’s which relied on a paid wait-list before any cars were actually built. As with Teslas, so with land. On these grounds, the networks state’s ‘digital first’ strategy can never be unearthly. Depending on the number of people that buy into exit via the networks state there may be enough willing sellers, leasers, or renters of land to fulfill the demand for land. Some of those people or groups might be sovereign Indigenous polities. At the same time, if networks state advocates are true to their ideological demand for respect of contract, then there are large portions of Earth that are spoken for in ways where market approaches to land may have little or no purchase.

In contrast to both the technate and the network state, Yarvin’s geographical imaginary of patchwork is thoroughly power politics forward. The transition to patchwork might use democratic means to insert its larval form in actually existing state institutions. But where Yarvin claims this would be but a beautiful ‘Butterfly Revolution’, my reading of his work and the people and ideas it associates with suggests the model in play is less butterfly, more wasp (CW: insect body horror).

Works Cited

“About Technocracy – Technocracy Inc. – Official Site.” n.d. Accessed April 28, 2025. https://technocracyinc.org/about-technocracy/.

Berkeley, Andrew, Josh Ryan-Collins, Asker Voldsgaard, Richard Tye, and Neil Wilson. 2024. “The Self-Financing State: An Institutional Analysis of Government Expenditure, Revenue Collection and Debt Issuance Operations in the United Kingdom.” SSRN Scholarly Paper. Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4890683.

Bounds, Leslie. 1947. “Old Man River.” The Northwest Technocrat, 1947.

Dryden, Joel. 2025. “Trump's Musings on 'Very Large Faucet' in Canada Part of Looming Water Crisis, Say Researchers.” CBC News, February 18, 2025. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/calgary/donald-trump-water-canada-peter-lougheed-1.7459583.

Finley, Klint. 2015. “Techies Have Been Trying to Replace Politicians for Decades.” Wired, June 5, 2015. https://www.wired.com/2015/06/technocracy-inc/.

Friedman, Milton. 1982. Capitalism and Freedom. University of Chicago Press.

Gleick, Peter H., Matthew Heberger, and Kristina Donnelly. 2014. “Zombie Water Projects.” In The World’s Water: The Biennial Report on Freshwater Resources, edited by Peter H. Gleick, 123–46. Washington, DC: Island Press/Center for Resource Economics. https://doi.org/10.5822/978-1-61091-483-3_7.

Graeber, David. 2011. Debt: The First 5,000 Years. Brooklyn, N.Y: Melville House.

Gregory, Derek. 2009. “Geographical Imaginary.” In The Dictionary of Human Geography. Blackwell Publishers. http://qe2a-proxy.mun.ca/Login?url=http://search.credoreference.com/content/entry/bkhumgeo/geographical_imaginary/0.

Haldeman, Joshua. 1940. “America Needs No Part of the Price System.” Technocracy Digest, July 1940.

Harman, Graham. 2014. Bruno Latour: Reassembling the Political. Pluto Press.

Harris, Malcolm. 2023. Palo Alto: A History of California, Capitalism, and the World. 1st ed. New York: Little, Brown and Company.

Hubbert, M. King. 1945. Technocracy Study Course Unabridged. 5th ed. http://archive.org/details/TechnocracyStudyCourseUnabridged.

Ivie, Wilton. 1957. “‘Adventure Into Fascism’ – Wilton Ivie – January 1947,” January 1957. http://archive.org/details/AdventureIntoFascism.

Kates, Sheridan. 2025. “How to Fight Back Against the False Idea That the Government Is at the Mercy of Financial Markets [Scotonomics Event].” THE ALTERNATIVE. March 7, 2025. https://thealternative.org.uk/dailyalternative/2025/3/10/scotonomics-monetary-autonomy.

Korosec, Kirsten, Zack Whittaker, Charles Rollet, Sean O’Kane, and Lorenzo Franceschi-Bicchierai. 2025. “The People in Elon Musk’s DOGE Universe.” TechCrunch (blog). February 25, 2025. https://techcrunch.com/2025/02/25/the-people-in-elon-musk-doge-universe/.

Latour, Bruno. 1993. We Have Never Been Modern. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

———. 2005. Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor Network Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lécuyer, Christophe. 2007. Making Silicon Valley: Innovation and the Growth of High Tech, 1930-1970. Massachusetts: MIT Press. http://mitpress.mit.edu/catalog/item/default.asp?ttype=2&tid=10631.

Leo, Geoff. 2025. “Tech-Utopian, Conspiracist and Apartheid Fan: Elon Musk’s Grandpa Was Shaped by Canadian Politics.” 2025. https://www.cbc.ca/newsinteractives/features/joshua-haldeman-elon-musk-saskatchewan-tech-utopian-conspiracist.

MMT Podcast with Patricia Pino & Christian Reilly, dir. 2025. #196 The Problem With Wealth Taxes with Steven Hail (Part 1). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1JqKp63WY-s.

Moldbug (aka Curtis Yarvin), Mencius. 2008. Patchwork: A Political System for the 21st Century. https://www.unqualified-reservations.org/2008/11/patchwork-positive-vision-part-1/.

Reisner, Marc. 1993. Cadillac Desert: The American West and Its Disappearing Water. Rev. and Updated. New York, N.Y., U.S.A: Penguin Books.

Scott, A. J, and D. P. Angel. 1987. “The US Semiconductor Industry: A Locational Analysis.” Environment and Planning A 19 (7): 875–912.

Scott, Howard. 1936. “Capitalizing Calamity.” Technocracy Magazine, May 1936.

———. 1939. “Pax Americana.” Technocracy, October 1939.

———. 1940. “Technate of America.” https://digital.library.cornell.edu/catalog/ss:34227574.

———. 1969. Gregory, John, Research Council of Alberta Correspondence with Howard Scott; Position and Statement Papers; Technocracy Paper on Continetnal Waterways; and Correspondence Related to the Continental Hydrology Pamphlet Review. http://archive.org/details/gregoryjohnresea00unse.

Southern Poverty Law Center. n.d.-a. “American Renaissance.” Southern Poverty Law Center. Accessed April 8, 2025. https://www.splcenter.org/resources/extremist-files/american-renaissance/.

———. n.d.-b. “Jared Taylor.” Southern Poverty Law Center. Accessed April 8, 2025. https://www.splcenter.org/resources/extremist-files/jared-taylor/.

Srinivasan, Balaji. n.d. The Network State: How to Start a New Country.

“Technocracy Fonds – Discover Archives.” n.d. Accessed April 28, 2025. https://discoverarchives.library.ualberta.ca/index.php/technocracy-fonds.

Technocracy Inc. 1937. “The Technocrat – Vol. 3 – No. 4 – September 1937,” September 1937. http://archive.org/details/TheTechnocrat-September1937.

———. 1945. Technocracy Study Course. http://archive.org/details/TechnocracyStudyCourse1945.

Tilove, Jonathan. 2006. “White Nationalist Conference Ponders Whether Jews and Nazis Can Get Along.” The Forward. March 3, 2006. https://forward.com/news/6615/white-nationalist-conference-ponders-whether-jews/.

You must be logged in to post a comment.