In 1854 in the Soho district of London England a cholera outbreak was killing people. You probably know this story. Its usually told with a physician named John Snow in the role of hero who hypothesized that the deaths in the area were caused by some sort of waterborne entity. Snow wasn’t sure what that entity might be, but he was a sceptic of the prevailing conjecture. He didn’t believe in the miasma theory of disease – – the hypothesis that airborne noxious fumes and polluting gases were the cause of illness. Although Snow didn’t know what the causal mechanism might be, research he had done earlier and published in an essay called On the Mode of Communication of Cholera pointed his suspicions at something to do with contaminated water rather than foul air.

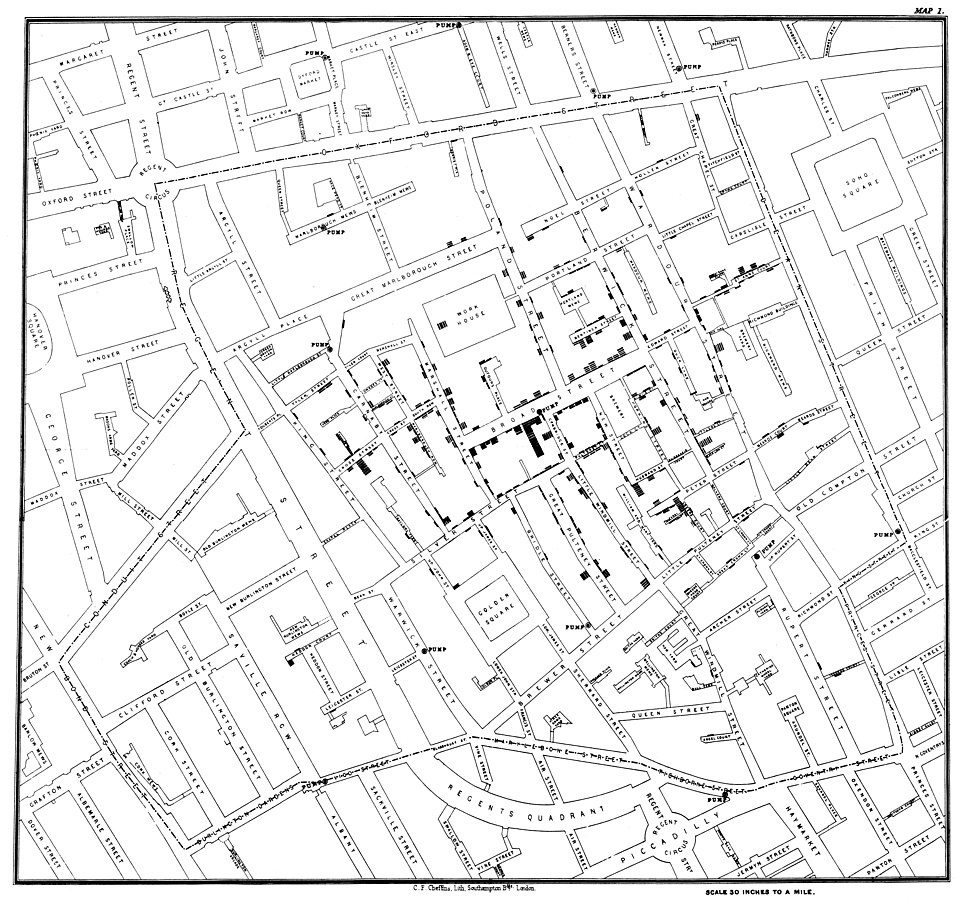

An alternative hypothesis, germ theory, would gain scientific consensus over the next 30 years or so, but at the time of the Soho epidemic the only things Snow had to go on were his scepticism of miasma theory and some preliminary microscopy of water samples. Snow under took chemical and microscopic investigation of water samples from the public water pump on Broad Street in Soho. These studies were inconclusive in terms of identifying a causal mechanism, but Snow also interviewed residents of the area and made maps of the deaths of people with symptoms of cholera. That something was causing deadly disease in the area was obvious, but the causal mechanism or mechanisms were up for debate.

The maps lead Snow to suspect the water pump at Broad Street as the likely source of disease. The cartographic evidence he produced also convinced the area council to remove the handle from the pump, rendering it in operable. The epidemic of cholera soon abated.

Snow’s research and the events of the Broad Street cholera epidemic are sometimes used as an illustration of the power of scientific research to provide unimpeachable evidence in favour of a decision to be made by politicians (e.g., the council deciding to remove the pump handle). Looking back from today we would understand that political decision as an uncontroversially beneficial public health outcome. But Snow’s intervention wasn’t that. Indeed, a substantial controversy ensued. Yes, the council permitted the removal of the Broad Street pump handle, but only temporarily. The council provisionally accepted Snow’s theory of water borne illness, but only until the cholera epidemic faded out. Then, the pump handle was replaced by the council partly because the miasma theory of disease was still prominent, partly because Snow’s theory was gross (poop in the water carried the disease vector), and partly because this was a public source of water for a population with little access to money and who could not afford to source their water from elsewhere.

A more accurate way to understand Snow’s intervention is as an example of what today we might understand as the precautionary principle (Harremoës et al. 2001, 14) – – even if that principle didn’t have a name during Snow’s time.

Snow was building his knowledge of the cholera outbreak when the miasma theory of disease was dominant. Alternatives, such as germ theory, were beginning to be articulated but, during the moment of the Broad Street cholera outbreak, they were still on the margins. Also, despite his investigations, Snow did not specifically identify a causal mechanism for the cholera outbreak. Again, he suspected it had something to do with a waterborne substance of some kind, but the bacterium that causes cholera wasn’t identified by Snow. A French naturalist, Félix-Archimède Pouchet, described the entity we now know as vibrio cholerae bacteria in 1849 the same year Snow published On the Mode of Communication of Cholera. But Pouchet wasn’t right either. He was a a proponent of yet another theory of disease called spontaneous generation and would go on to debate against Louis Pasteur who advocated germ theory. Pasteur did crucial and very controversial work on what we now call vaccines and, yes, pasteurization (Latour 1988).

Isolating vibrio cholerae as a specific bacterial species was accomplished not by Snow, nor by Pouchet nor Pasteur, but by an Italian scientist, Filippo Pacini. And, linking the bacterium vibrio cholerae as the cause of the disease cholera wasn’t accomplished until 30 years after the Broad Street outbreak when German physician and microbiologist Robert Koch — also a critic of Pasteur’s research–would be credited with the connection. Even then it wasn’t until the mid-20th century when, in 1959 (more than 100 years after the Broad Street cholera outbreak), Dr. Shambhu Nath De isolated the specific toxin produced by vibrio cholerae as the actual causal mechanism for the disease cholera.

All of this is to say that in his day, Snow was operating under conditions of wild uncertainty and ignorance. He had a hypothesis about waterborne illness, but nothing conclusive about the actual causal mechanism(s). His recommendation to remove the handle from the public water pump was premised on what some data – – maps of deaths from cholera in the area – – suggested as a possible intervention, but offered no conclusive cause and certainly not proof (only mathematicians get to operate under that condition of possibility).

Removing the Broad Street pump handle was controversial. The area council had immediate concerns for the people in the neighbourhood who were dying of cholera, but they had other short term concerns as well: water is a necessity of life and people in the area had little ability to afford water from an alternate source. As soon as the cholera epidemic subsided sufficiently, the council replaced the handle on the Broad Street pump. The political decision to intervene at the pump was a precautionary move, rather than one premised on the clearing away of uncertainty and doubt by the application of scientific research. The precautions taken at the Broad Street pump in 1854 were controversial in their time and place. Controversy and precaution remain co-travellers. Recently, the “precautionary principle” was literally named as a member of “The Enemy” in Mark Andreessen’s The Techno-Optimist Manifesto (Andreessen 2023). When it was published two years ago the manifesto might’ve been dismissed as just a quirky blog post by one of Silicon Valley’s elite venture capitalists. Today, such dismissal seems foolhardy. Just before Trump’s inauguration, Andreessen referred to himself as an “unpaid intern” at DOGE, for example, and he has since become a key advisor to, and recruiter for, the political coalition undertaking the ongoing coup in the United States (Korosec et al. 2025).

According to Andreessen’s (2023) Manifesto:

Our enemies are not bad people – but rather bad ideas.

Our present society has been subjected to a mass demoralization campaign for six decades – against technology and against life – under varying names like “existential risk”, “sustainability”, “ESG”, “Sustainable Development Goals”, “social responsibility”, “stakeholder capitalism”, “Precautionary Principle”, “trust and safety”, “tech ethics”, “risk management”, “de-growth”, “the limits of growth”.

This demoralization campaign is based on bad ideas of the past – zombie ideas, many derived from Communism, disastrous then and now – that have refused to die.

Such an enemy list is quite a collection of ideas. Andreesen’s loathing of ‘stakeholder capitalism’ offers yet another data point bolstering the observation that capitalists hate capitalism. Meanwhile, his assertion that many of these ‘bad ideas’ have their roots in communism sounds an awful lot like a just-so story written by Ayn Rand. Neither the word “precaution” nor the phrase “precautionary principle” appears in Rand’s Introduction to Objectivist Epistemology, nor her anti-environmentalist book The Anti-Industrial Revolution, nor in The Ayn Rand Lexicon. But reading Julia Burns’ (2023) biography of Ayn Rand it’s possible to see in Andreessen’s manifesto a kind of objectivist throughline in what otherwise might seem like an enemies list composed more of an idiosyncratic laundry list of grievances than logical coherence. Rand herself might not have written against the precautionary principle, but commentators at the Rand-inspried Atlas Network do (Kazman 2010), just as they also comment on it in Andreesen’s Manifesto (Tracinski 2024).

Taking the claim of a six decade onslaught in Andreesen’s manifesto literally plants the golden spike at 1963. Perhaps it’s a coincidence that Rand’s Atlas Shrugged, published in 1957, lies just outside Andreessen’s timeline, but Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring and her 1963 testimony before Congress marks what would be that timeline’s beginning. Carson was, of course, spared no amount of criticism for ostensibly being a Communist, crypto- or otherwise (Lear 1997). But, it’s a misapprehension of the history of what we now sum up under the term ‘environmentalism’ to plant the golden spike at Silent Spring. Was the publication of that book and the Carson’s public role important? Yes. But even in the crucial years between 1963 and the first Earth Day in in 1970 it was a coalition of not very similar parties that found ways to work toward concrete political demands for regulating chemicals and pesticides based on the precautionary principle. That work was done with a coalition held together in part by strong worker-led actors, especially the UAW, who worked explicitly in coalition with students and members of the growing suburban white middle-class (Montrie 2018).

The origin of the ‘bad idea’ of the precautionary principle at work in contemporary US regulations is traced by environmental historian Nancy Langston (2014) to the passage of the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act signed into law by Roosevelt in 1938. So, it is accurate to place the idea’s relevance to a broader environmental movement within a longer historical context beyond Silent Spring. But it is also accurate to note that it was the statism of the New Deal period that formed (and remains) one of the most potent targets of Rand and her acolytes.

The hardware and software of computing technology is the ‘tech’ at the core of Andreesen’s manifesto, but he comes to this tech as a software engineer. According to his own writing, the “real-world” (his term) is “being eaten by software”. But there is no software without hardware and building the hardware of computer technology is an industrial manufacturing process–with all the chunky solid, liquid, and gaseous ‘real world’ inputs and outputs that kind of production implies. Chemical inputs are especially important. Many of those chemicals are toxicants. One key class of such chemicals is per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), also dubbed ‘forever chemicals’. PFAS are critical intermediate inputs for making semiconductors. Semiconductors are the substrate on which all contemporary computing is premised. Without semiconductors there are no hardware and without hardware there is no software.

Toxicologists and chemical manufacturers have been battling for years over the degree of harm PFAS represent. In one sense, both groups agree with one another: PFAS are toxicants that cause harm. Where toxicological scientists and industry lobbyists disagree is on how harmful these toxicants are and how to balance the utility of these chemicals with the harms known–and unknown–to arise from them. Toxicologists invoke the precautionary principle as one means to navigate the assessment of the relative merits and the demerits of PFAS. Industry places a strong emphasis on the widespread use of PFAS in a variety of applications they deem “critical to modern life” (pointing to everything from airplanes to automobiles to cell phones; see Bowman 2015).

Andreesenites think they know the enemy here: it’s the toxicologists, the scientists advocating from the ‘bad idea’ of the precautionary principle. The thing about political coalitions though is that they’re hard. Ways have to be found to smooth over the fracture lines that exist in any such coalition, even one that may from the outside appear to be in complete alignment as it actively dismantles the administrative and regulatory state, including institutions key to chemicals regulation such as the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Yet points of fracture do indeed exist. The precautionary principle and PFAS is one of them.

Members of the coalition undertaking the coup in the United States include those who might be described as the tech right — bundled under the auspices of DOGE — and Christian nationalists, perhaps best represented by the Heritage Foundation and its Project 2025. As a tech right-ist, Andreesen’s designation of precaution as an enemy accords with parts of Project 2025, even as it jars with internal contradictions explicitly evident in the project’s published plans. PFAS are explicitly discussed in the 900+ page Project 2025 document, but that discussion is one among many instances of advocacy for mutually exclusive desires.

With one hand, Project 2025 advocates for government intervention to “[r]evise groundwater cleanup regulations and policies to reflect the challenges of omnipresent contaminants like PFAS” (Dans and Groves 2023, 431). ‘Let us be cautious about omnipresent contaminants like PFAS!’, yells this part of the coalition. With the other hand, members of the same coalition advocate against government intervention and seek to “[r]evist the designation of PFAS chemicals as ‘hazardous substances’ under CERCLA” (Dans and Groves 2023, 431). ‘Don’t let’s be worrywarts — all ahead full!’, yells another part of the same coalition. What this situation makes obvious is that the desires holding together this odious coalition are neither perfectly aligned nor monolithic.

Imperfect alignments are tactically useful. They can be exploited. The precautionary principle and its relations with PFAS are some points of purchase by which seemingly aligned interests might be wedged apart. Open the cracks enough and the coalition can collapse under the weight of its own internal contradictions.

Making semiconductors is a very technically challenging project. Today, semiconductors are composed of circuitry physically etched into patterns that are so small that they can collapse if conditions aren’t just right. The industry has a name for this. It’s called ‘pattern collapse’. It happens when the surface tension of fluids used in semiconductor manufacturing is enough to warp the physical shapes of the circuitry being etched. If pattern collapse happens, a semiconductor is rendered non-functional. The risk of pattern collapse is why PFAS are needed in semiconductor manufacturing. PFAS are really good at reducing surface tension. By reducing surface tension PFAS solve the problem of pattern collapse.

Perhaps there’s a metaphor in there.

Understanding PFAS and the precautionary principle as points of purchase for wedging apart a coalition of power might offer a way to collapse a pattern of power that might otherwise appear as an overwhelming, monolithic, and oppressive edifice. Are they enough on their own? Of course not. That’s just all the more reason to search out and find more ways to induce pattern collapse. Could attacking such points of internally discordant desires of an opponent work? Just like John Snow, there’s no knowing in advance. There’s only wild uncertainty, ignorance, and perseverance in the face of them.

Works Cited

Andreessen, Marc. 2023. “The Techno-Optimist Manifesto.” Andreessen Horowitz. October 16, 2023. https://a16z.com/the-techno-optimist-manifesto/.

Bowman, Jessica S. 2015. “Fluorotechnology Is Critical to Modern Life: The FluoroCouncil Counterpoint to the Madrid Statement.” Environmental Health Perspectives 123 (5): A112–13. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1509910.

Burns, Jennifer. 2023. Goddess of the Market: Ayn Rand and the American Right. Oxford Scholarship Online. Oxford ; Oxford University Press.

Clark, Jonathan L. 2015. “Uncharismatic Invasives.” Environmental Humanities 6 (1): 29–52. https://doi.org/10.1215/22011919-3615889.

Dans, Paul, and Steven Groves, eds. 2023. Mandate for Leadership: The Conservative Promise. Washington, DC: The Heritage Foundation.

Harremoës, Poul, David Gee, Malcolm MacGarvin, Andy Stirling, Jane Keys, Brian Wynne, and Sofia Guedes Vaz. 2001. “Late Lessons from Early Warnings: The Precautionary Principle, 1896-2000.” 22. Environmental Issue Report. Copenhagen: European Environment Agency. https://www.iatp.org/sites/default/files/Late_Lessons_from_Early_Warnings_The_Precautio.pdf.

Kazman, Sam. 2010. “Better Never?, The Atlas Society | Ayn Rand, Objectivism, Atlas Shrugged.” August 22, 2010. https://www.atlassociety.org/post/better-never.

Korosec, Kirsten, Zack Whittaker, Charles Rollet, Sean O’Kane, and Lorenzo Franceschi-Bicchierai. 2025. “The People in Elon Musk’s DOGE Universe.” TechCrunch (blog). February 25, 2025. https://techcrunch.com/2025/02/25/the-people-in-elon-musk-doge-universe/.

Langston, Nancy. 2014. “Precaution and the History of Endocrine Disruptors.” In Powerless Science? Science and Politics in a Toxic World, edited by Soraya Boudia and Nathalie Jas, 29–45. The Environment in History: International Perspectives, volume 2. New York: Berghahn Books.

Latour, Bruno. 1988. The Pasteurization of France. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Lear, Linda J. 1997. Rachel Carson: Witness for Nature. 1st ed. New York: H. Holt.

Montrie, Chad. 2018. The Myth of Silent Spring: Rethinking the Origins of American Environmentalism. Oakland, California: University of California Press. Tracinski, Robert. 2024. “The Disreputable Optimist, The Atlas Society | Ayn Rand, Objectivism, Atlas Shrugged.” October 28, 2024. https://www.atlassociety.org/post/the-disreputable-optimist.

You must be logged in to post a comment.