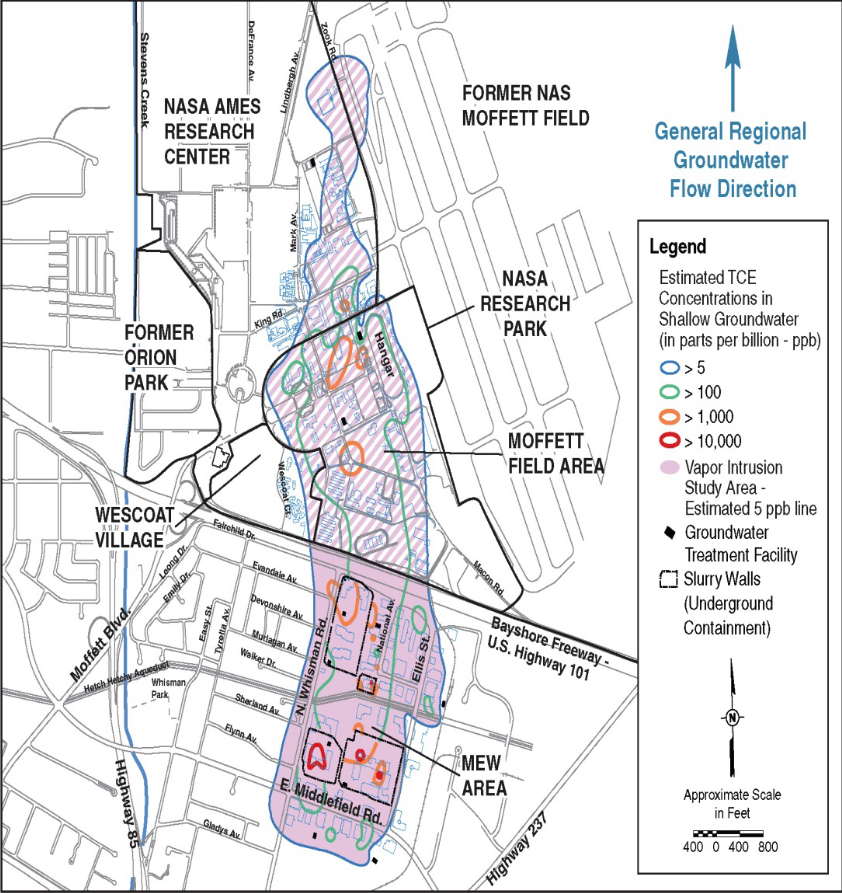

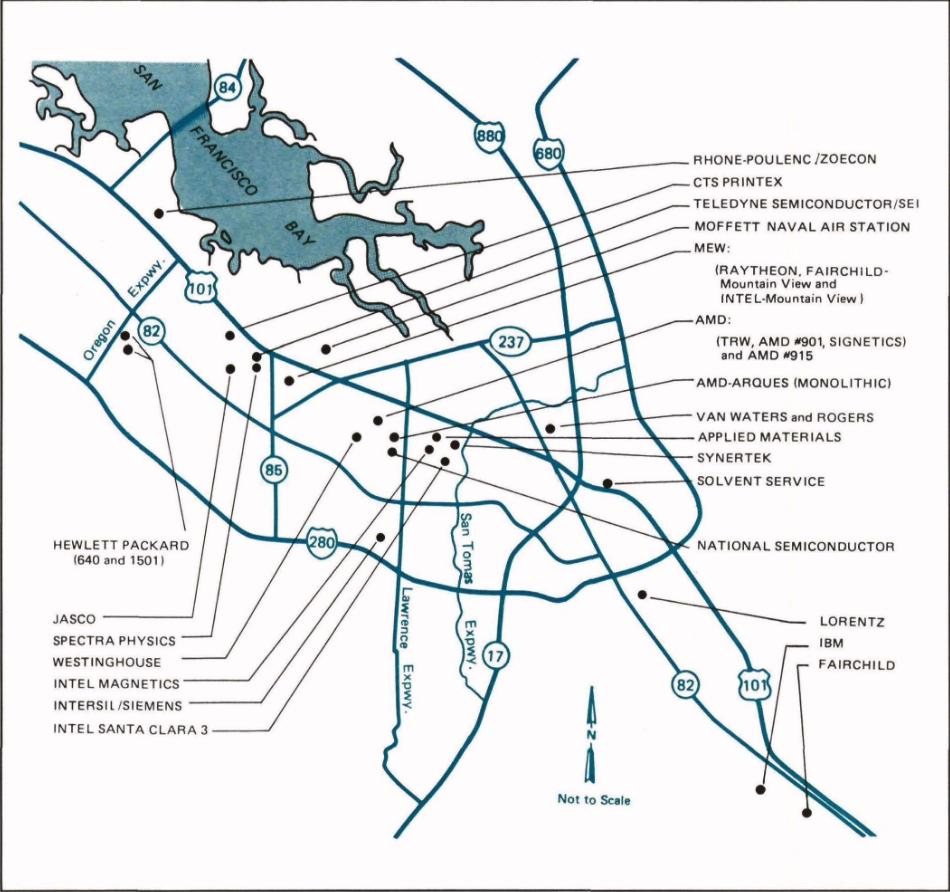

Santa Clara county, California, where today sits Silicon Valley, is home to the largest number of Superfund sites of any county in the United States. ‘Superfund’ is the federal program that empowers the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to clean up sites contaminated by industrial pollution in circumstances where the responsible entity (or entities) no longer exist (e.g., because they’ve gone bankrupt or have merged with other companies and have ceased to have legal existence). Many of the Superfund sites in Santa Clara County are legacies of the region’s history of electronics manufacturing. One of the most infamous of these sites is the Middlefield-Ellis-Whisman (MEW) study area (United States Environmental Protection Agency 1989a).

MEW gets is name from three of the roads that compose its southern border. Its infamy stems from it being a surface location of a large plume of groundwater polluted by some of the key companies that led to Silicon Valley being called Silicon Valley: Fairchild Semiconductors, Intel, and Raytheon (Siegel 1982). The plume of contaminated groundwater is an unintentional result of intentional building design codes that strictly mandated industrial infrastructure, such as storage tanks, to be buried underground where they would not interfere with the visual landscape aesthetic desired by the Valley’s champions. Among those champions was Frederick Terman. Terman–whose father Lewis was a prominent eugenicist who did foundational work on ‘IQ’ testing–became dean of the School of Engineering at Standford. In that role Terman helped develop what was then a novel idea for jumpstarting industrial development: the creation of park-like industrial spaces that would differentiate themselves from the scourges of “soot and rowdy laborers” he associated with the industrial cities of the East Coast (Sachs 1999, 16). These ‘industrial parks’ –a new idea in the mid-1950s–were seen by Terman and Standford Business manager Alf E. Brandon as a way to “attract a better class of workers”, which meant almost exclusively “well-to-do white males” in the engineering professions, as environmental historian Aaron Sachs point out (Sachs 1999, 16; for a rich history of the foundational role eugenics plays in today’s Silicon Valley milieu, see Harris 2023). Terman insisted that these industrial parks conceal their necessary industrial components out of view. That meant placing underground things like storage tanks for chemicals necessary in the manufacturing of semiconductors. Those landscape design decisions kept those tanks and other infrastructure out of sight, but also increased the risk that leaks or failures of tanks pipes might go unnoticed for a considerable period of time. Eventually, this is exactly what came to pass.

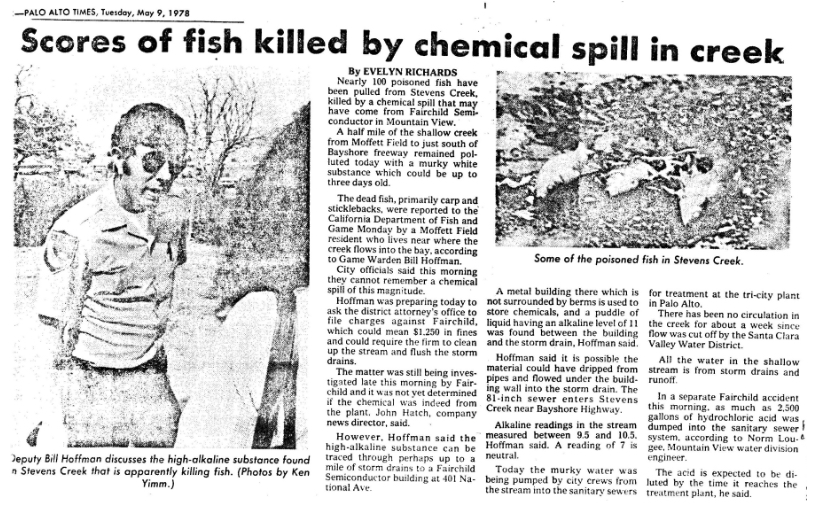

Many of the chemicals used in electronics manufacturing, including the sites at Fairchild Semiconductors, Intel, Raytheon are acidic. Overtime, those chemicals ate through the walls of storage tanks and pipes that enabled their flow throughout the manufacturing process. Those tanks and pipes were already largely underground, so leaks lead to chronic spills of toxicants into the region’s subsurface geology and hydrology. The toxic effects of those leaks began to show up in news reports in 1978.

By 1982, 21 leaks were identified at multiple facilities leading the California Regional Water Control Board to initiate a leak detection program (Olivieri et al. 1985). By 1989, the EPA had declared the MEW area and 28 other locations in the region as Superfund sites (United States Environmental Protection Agency 1989b).

United States Environmental Protection Agency (1989b, 3).

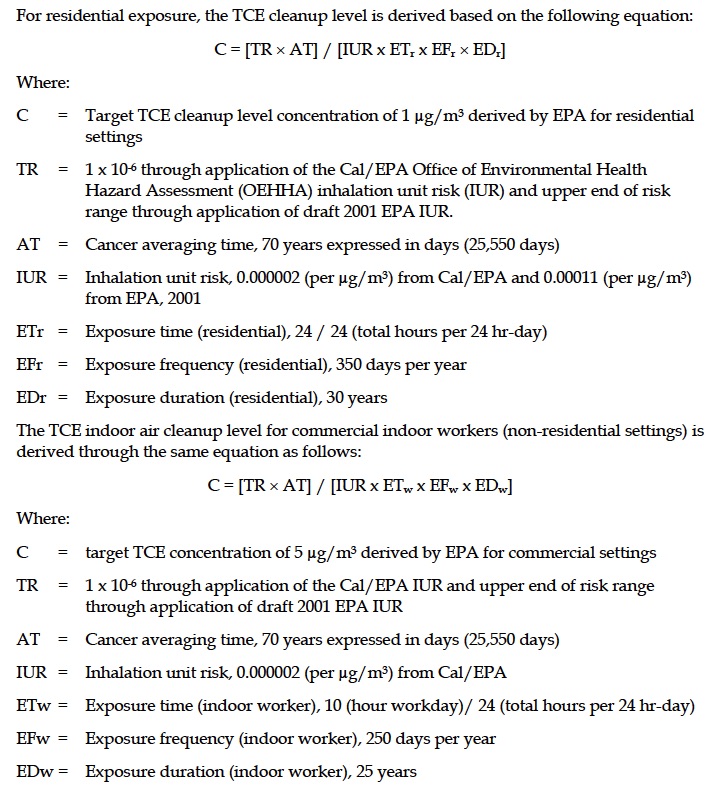

At the MEW site a key chemical of concern is trichloroethylene (TCE), a solvent used in various phases of electronics manufacturing. Over the two decades between 1989 and 2010, the EPA would go on to define a variety of mitigation measures for TCE contamination of air and groundwater in the MEW zone (Lepawsky 2023). Part of that process involved defining thresholds dividing acceptable and unacceptable levels of TCE due to cancer risk. Two such thresholds were defined, one for shallow and one for deep aquifers at 5 parts per billion (ppb) and 0.8 ppb respectively (deep aquifers are sources of drinking water, hence the lower threshold). The precision of these numbers belies some important arbitrary decisions used to arrive at them. The 0.8 ppb threshold was determined by, “multiplying a concentration by 2 liters per day and dividing by 70 kilograms” (United States Environmental Protection Agency 1989a, 20). Those multiplications were entered into two equations developed to determine TCE mitigation requirements in commercial/industrial spaces and in residential spaces in the MEW zone. Here are the equations:

There are always trade-offs with turning lived realities into data, including in the form of numbers (Nguyen 2024). Those trade-offs don’t mean data are inherently good or bad, but they do mean data are never neutral either. Let’s look at those numbers calculated for the threshold of TCE. A person who drinks 2 L of water a day and weighs 70 kg is not just a generic human. At the very least, the calculation for lifetime average daily dose (or LADD) excludes those who weigh less (or more) than 70 kg. Those in the less than 70 kg category would include infants and many children, for example. There are other important non-neutral decisions made in calculating the LADD for TCE in the MEW zone. Notice, for example, that in the residential calculation for exposure, exposure time is assumed to be constant (24 hours per day) over most of a year (350 days). Meanwhile, exposure time in commercial/industrial settings is assumed to be 10 hours per day, over 250 days per year, over a working life of 25 years. One could point to all of these assumptions as arbitrary in some way or other–350 days implies 16 days away from home which sounds an awful lot like ‘2 weeks holiday’. That might be a convenient assumption, but is it an accurate one for people who live in the MEW? Similarly, 250 work days per year sounds like 5 days on, 2 days off, and 2 weeks vacation. For whom and how many people is such a work schedule relevant then and now? Again, these may be convenient assumptions but are they accurate? Maybe. But there’s something more fundamental going on in how these calculations are set up. Notice that there are two separate calculations, one for people exposed to TCE at work and one for people exposed for TCE at home. Yet neither calculation even considers that people can be exposed to TCE both at work and at home. The calculations offer no way to meaningfully combine those exposure risks. Again, the trade-offs made here (i.e. the assumptions) don’t make the equations or the resulting data bad per se. Assumptions do have to be made. That’s unavoidable. But, the assumptions do make the calculations and the data approach to exposure mitigation in ways that favour some people’s daily lives and disfavour others. Even precautionary approaches are partial.

‘Partial’ and ‘partisan’ share an etymological root and there is an interesting geographical coincidence between the roots of Silicon Valley’s family tree, represented by the former Fairchild, Intel, and Raytheon sites in the MEW, and new(er) (though now ‘old’) tech startups. Netscape, an early internet browser, had its headquarters at 501 Middlefield Road, right in the midst of the MEW. There’s nothing nefarious about that. The toxicants in the MEW plume were released long before Netscape’s presence there and Netscape was a software company, it wasn’t producing electronics (although Netscape, like all software companies, is utterly dependent on hardware and its legacies, including pollution). The connection here, such as it is, is geographical coincidence: people in buildings like the former Netscape headquarters have been subject to exposures of toxic vapours emanating from the spills in the ground water beneath them. Google employees at the Google Quad Campus just down the street from 501 Middlefield were exposed to “levels of trichloroethylene (TCE) in the air [that] well exceeded concentrations that would be considered safe” (Guest 2013) between 2012 and 2013 (see also Rust and Drange 2013).

One of the people recruited to found Netscape was Marc Andreesen, now known for his venture capital firm. He is also author of the ‘Techno-Optimist Manifesto’ published by Marc Andreessen (Andreessen 2023). If you haven’t read this manifesto, it is a wild document. Even as it explicitly claims to be about a “material philosophy, not a political philosophy” it proceeds to make the claim that “material abundance from markets and technology opens the space for religion, for politics, and for choices of how to live, socially and individually.” (Andreessen 2023). Synonyms for a ‘political’ include ‘activist’ and ‘partisan’ and the manifesto is, on its own terms, partisan: it is a statement of support for techno-optimism. Whats more, it defines what it calls “The Enemy”. That enemy is “not bad people – but rather bad ideas” (Andreessen 2023). And among those ideas are the precautionary principle (not to mention a slew of other bogeys such as ”Communism […] statism, authoritarianism, collectivism, central planning, socialism” (Andreessen 2023)).

TCE is a known carcinogen and the EPA’s regulation of it is explicitly premised on a precautionary approach, but the precautionary approach did not begin with the EPA’s regulation of TCE. In a detailed chapter on the history of the precautionary principle in US regulatory frameworks for toxic chemicals, Nancy Langston (2014) shows that principle was part of the regulatory discussion by 1938 with the passage of the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act. That history places ‘precaution’ within the wider conflicts over the New Deal. If the ‘precautionary principle’ is an idea of The Enemy, then perhaps it is not coincidental that the Techno-Optimist Manifesto resonates so strongly with the more reactionary, anti-statist business class who opposed the New Deal. Andreesen’s manifesto is in this vein and works in coalition with other centres of power aligned with Trump’s rise, like the National Manufacturers Association (2024) and Project 2025 (Dans and Groves 2023).

As Cory Doctorow (2024) notes, coalitions are hard. Andreesen’s manifesto explicitly names the precautionary principle as a member of ‘The Enemy’. NAM and Project 2025 demarcate The Enemy is some ways that are similar, but all of these coalition partners offer internally contradictory desiderata within and between their expressly stated hopes and dreams for the world they want. Contradictions are weak points in the networks holding political coalitions together. They can be exploited and heightened to weaken, even destroy, the bonds holding such coalitions together. Desires explicitly and implicitly expressed for chemical regulations by these coalition partners are one of those areas of internal contradiction.

Project 2025 appears contradictory on chemical regulations in its chapter on the Environmental Protection Agency. With one hand it recommends to “[r]evise groundwater cleanup regulations and policies to reflect the challenges of omnipresent contaminants like PFAS.” (Dans and Groves 2023, 431) . With the other it advocates to “[r]evist the designation of PFAS chemicals as ‘hazardous substances’ under CERCLA.” (Dans and Groves 2023, 431). On the one hand PFAS, a class of chemicals containing millions of individual compounds, are forthrightly described as contaminants. In the next sentence the very status of PFAS as hazardous is to be revisited which at least implies that PFAS are not contaminants. Meanwhile, the National Association of Manufacturers (NAM) seeks relief from the “onslaught” of regulations against chemical manufacturers (National Association of Manufacturers 2024, 10). In particular, NAM wants the Trump administration to “pause” rulemaking regarding PFAS and take an “incremental approach” (i.e., chemical by chemical) to PFAS. There are so many individual chemicals just within the category of PFAS that there will never be enough to investigate each one individually for their toxic potentials. If chemicals were kilometers, then as of 2025 there are enough chemicals available for industrial uses that they would stretch from Earth around the Sun and back. The number of chemicals managed to be tested for various forms of toxicity – – about 196,000 – – have all been found to be toxic in one way or another, but if these chemicals were kilometres they would only stretch from Earth halfway to the Moon. An incremental approach enhances the power chemical manufacturers already have to decide the chemical fate of products in the environments in which they are manufactured, used, and dissipate will be in the hands of those that make the chemicals.

There are other ways chemical regulation could go. It is already the status quo that multibillion dollar industry is like automobile manufacturing or food and pharmaceuticals have to demonstrate that their products are safe within certain limits before they are allowed to be manufactured and sold on the market. This situation did not happen by itself nor did it happen as a consequence of the benevolent actions of enlightened corporations. Before it was mandatory for there to be seatbelts, for example, and oligopoly of US car manufacturers advocated for voluntary rules for safety. Citizens, on the other hand, organized collectively for political power such that the US federal government was forced to wrest control away from those corporations and make safety requirements a matter of legislation (and created an institution – – the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration — to enforce that legislation).

Andreesen-ite techno-optimists, Project 2025’ers, and NAM’ists want complementary but also contradictory things. In the process they are just recycling a mish-mash of pro-business, anti-statist tropes, earnestly in play since at least the days of the New Deal (Oreskes and Conway 2023). What this coalition of interests shares is pretty basic: a desire for them to be unbound by regulation themselves yet be protected by legal fetter from those they deem to be their enemies. Making a list of their contradictory interests can be clarifying. It can be part of a process of identifying alternatives to the enhancement of private, non-democractic corporate power over and above everyone else. Toxicants in general, and PFAS specifically, appear to be one of those contradictory nodes in their coalitional network. Some members of the coalition want clean up of groundwater so that it is free of “omnipresent contaminants like PFAS”. When it comes to a foundational technology of the tech industry itself, desire for a PFAS free world is an impossibility. All ‘tech’ companies must pass through the obligatory passage point of semiconductors. PFAS are used to make semiconductors. There appear to be no alternatives to PFAS use in some stages of that manufacturing (Lay et al., nd, 20). If tech is a foundational technology, then coalitions like these business interests that see environmental regulations as hindrances that must be demolished, one possible response would be to ask them to name the applications and sectors from which they are willing to eliminate PFAS use to get their revisions of regulations and policies they want so to have PFAS free groundwater. Those amongst the coalition with opposing interests in this regard can be encouraged to fight amongst themselves and weaken their sense of shared interests.

Works Cited

Andreessen, Marc. 2023. “The Techno-Optimist Manifesto.” Andreessen Horowitz. October 16, 2023. https://a16z.com/the-techno-optimist-manifesto/.

Dans, Paul, and Steven Groves, eds. 2023. Mandate for Leadership: The Conservative Promise. Washington, DC: The Heritage Foundation.

Doctorow, Cory. 2024. “Pluralistic: The True, Tactical Significance of Project 2025 (14 Jul 2024) – Pluralistic: Daily Links from Cory Doctorow.” May 2, 2024. https://pluralistic.net/2024/07/14/fracture-lines/.

Guest, H. W. E. 2013. “TCE Concerns for Google.” Hazardous Waste Experts (blog). November 6, 2013. https://www.hazardouswasteexperts.com/trichloroethylene-tce-concerns-for-google-employees/.

Harris, Malcolm. 2023. Palo Alto: A History of California, Capitalism, and the World. 1st ed. New York: Little, Brown and Company.

Langston, Nancy. 2014. “Precaution and the History of Endocrine Disruptors.” In Powerless Science? Science and Politics in a Toxic World, edited by Soraya Boudia and Nathalie Jas, 29–45. The Environment in History: International Perspectives, volume 2. New York: Berghahn Books.

Lay, Dean, Ian Keyte, Scott Tiscione, and Julius Kreissig. n.d. “Check Your Tech: A Guide to PFAS in Electronics.” ChemSec. Accessed October 4, 2023. https://chemsec.org/app/uploads/2023/04/Check-your-Tech_230420.pdf.

Lepawsky, Josh. 2023. “Mitigating Durable Bads: Trichloroethylene Contamination in Silicon Valley.” In Durable Economies: Organizing the Material Foundations of Society, edited by Melanie Jaeger-Erben, Harald Wieser, Max Marwede, and Florian Hofmann, 49–70. Labor and Organization, volume 10. Bielefeld: transcript. https://doi.org/10.14361/9783839463963.

National Association of Manufacturers. 2024. “Manufacturers Regulatory Letter to President Elect Trump.” https://www.nam.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/Manufacturers-Regulatory-Letter-to-President-Elect-Trump_12.5.24.pdf.

Nguyen, C. Thi. 2024. “The Limits of Data.” Issues in Science and Technology 40 (2): 94–101. https://doi.org/10.58875/LUXD6515.

Olivieri, Adam, Don Eisenberg, Martin Kurtovich, and Lori Pettegrew. 1985. “Ground‐Water Contamination in Silicon Valley.” Journal of Water Resources Planning and Management 111 (3): 3546–358. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9496(1985)111:3(346).

Oreskes, Naomi, and Erik M. Conway. 2023. The Big Myth: How American Business Taught Us to Loathe Government and Love the Free Market. Bloomsbury Publishing USA.

Rust, Susanne, and Matt Drange. 2013. “Google Employees Face Health Risks from Superfund Site’s Toxic Vapors | The Center for Investigative Reporting.” March 25, 2013. http://cironline.org/reports/google-employees-face-health-risks-superfund-sites-toxic-vapors-4291.

Sachs, Aaron. 1999. “Virtual Ecology.” World Watch, February 1999.

Siegel, Lenny. 1982. Background Report on Silicon Valley. Pacific Studies Center.

———. 2013. “Mountain View, California’s Mystery TCE Hotspots.” Center for Public Environmental Oversight. http://www.cpeo.org/pubs/MVHotspots.pdf.

United States Environmental Protection Agency. 1989a. “Fairchild, Intel, and Raytheon Sites Middlefield/Ellis/Whisman (MEW) Study Area Mountain View, California | Record of Decision.” https://www.nasa.gov/sites/default/files/atoms/files/record_of_decision_mew_study_area_june_1989.pdf.

———. 1989b. “Groundwater Contamination Cleanups At South Bay Superfund Sites.” San Francisco: United States Environmental Protection Agency. https://nepis.epa.gov/Exe/ZyPURL.cgi?Dockey=9100976C.txt.

———. 2010. “Record of Decision Amendment for the Vapor Intrusion Pathway | MIDDLEFIELD-ELLIS-WHISMAN (MEW) SUPERFUND STUDY AREA Mountain View and Moffett Field, California.” https://www.nasa.gov/sites/default/files/atoms/files/rod_amendment_mew_vi_august_2010.pdf.

You must be logged in to post a comment.