US geopolitical worries, largely focused on rivalry with China, have given permission for the federal government to offer an overt industrial policy for semiconductor manufacturing. The US has embarked on a massively state funded program to bring semiconductor manufacturing capacity back to the continent after decades of offshoring (the EU is doing this too). In 2022 the United States passed the “Creating Helpful Incentives to Produce Semiconductors” [CHIPS] Act. CHIPS earmarks around $300 billion to support reinvestment in semiconductor manufacturing in the US.

US (and EU) geopolitical worries are mostly framed in classic terms of international relations and political geography–think inter-state rivalry between the US and China in a “Chip War”. Whatever one may think of such rivalries, something those concerns are mostly silent on are the environmental impacts of making tech like semiconductors.

Despite this relative silence on environmental issues in the chip wars discourse, the CHIPS Act is subject to environmental impact assessment regulations. This means that both the program itself and any individual project considered for funding under it must submit an environmental assessment document. In turn, these documents provide detailed insights into the anticipated environmental impacts of semiconductor manufacturing projects in the US.

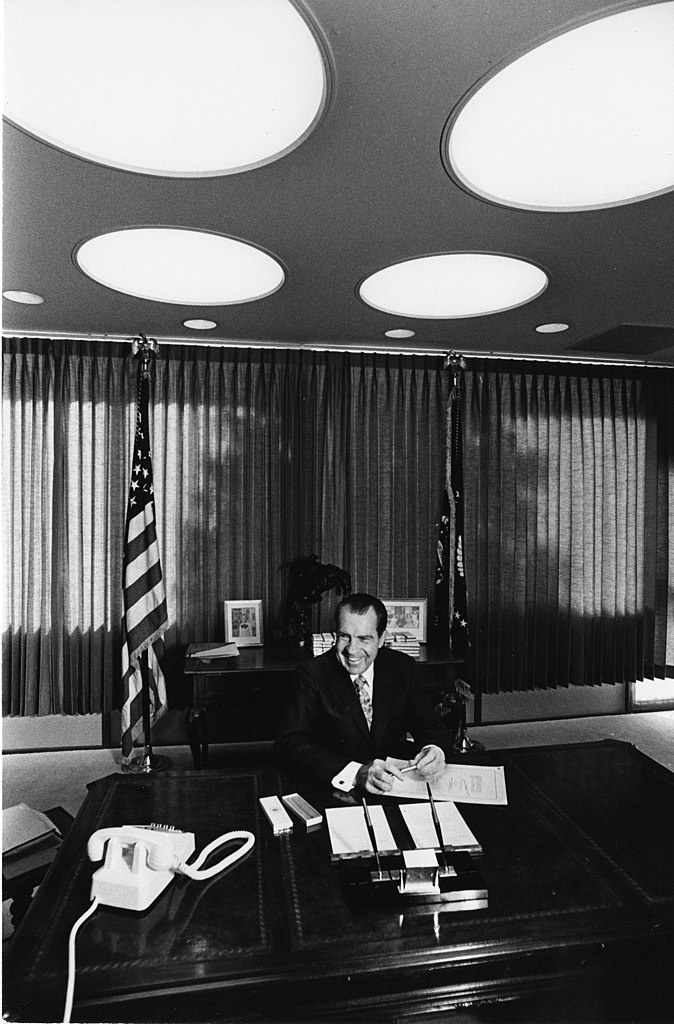

The Department of Commerce [DOC] and its National Institute of Standards and Technology [NIST] are the principal federal agencies administering CHIPS. Under legislation signed into law by President Nixon in 1970, all federal agencies are subject to the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) under United States Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) Title 40 (“Protection of the Environment”, 40 CFR 1500.1).

Thanks to NEPA, DOC and any semiconductor manufacturers that may receive CHIPS funds must submit environmental impact assessments of their proposed projects (thanks to a 1988 Supreme Court decision there is no duty on federal agencies to mitigate negative environmental effects or even to develop a mitigation plan for them; see Stevens, 1988). Although dry and procedural, the environmental assessment documents submitted by DOC and the companies seeking CHIPS funding offer enormous potential for critical analyses, including both qualitative and quantitative sources of numerical, rhetorical, and spatial data. DOC published its Programmatic Environmental Assessment (pdf, >3MB) in December 2023. TSMC, Intel, and Micron followed in the first few months of 2024. All of these assessments arrive at a Finding of No Significant Impact (“FONSI”, yes, this is an actual acronym under 40 CFR 6.206; no, it is not about this guy).

How do these environmental assessments arrive at a FONSI? What does such a finding actually mean in these specific environmental assessments for DOC and for the three companies that have submitted environmental assessments so far (TSMC, Intel, and Micron)?

TL;DR

The Department of Commerce arrives at a FONSI via five types of justification:

1) Misleading comparisons and false equivalencies. For example, DOC compares emissions from individual semiconductor facilities to emissions from the entire semiconductor sector and to the US as a whole. Such comparisons make the emissions from an individual facility appear insignificant.

2) Recognition and dismissal of known effects. For example, DOC’s assessment recognizes even with improvements in efficiency and waste management that increases in semiconductor manufacturing will also result in increases in pollution and waste (e.g. emissions; aka the rebound effect or Jevons paradox). While recognized, these effects are simply waved away with a faith in solutionism (see below).

3) Scalar mismatch or a misalignment between identified problems and solutions. A good example of this appears in the DOC’s discussion of chemical pollution from the semiconductor industry, particularly per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS). DOC’s assessment relies on a threshold here theory of harm, yet some PFASs can cause harm on contact rather than after exceeding some lower limit.

4) Faith in regulatory capacity and enforcement. The application of environmental and occupational health and safety regulations have been under chronic attack for at least 40 years (Oreskes and Conway, 2023), but that attack has intensified since the US Supreme Court overturned Chevron (United States Supreme Court, 2024; United States Supreme Court, 1984).

5) Faith in technological solutionism (e.g., treatment of hazardous materials and waste; water recycling efficiency) or, “a theory of change that posits that a social problem can be ‘solved’ deterministically by a technological design.” (Angel and Boyd, 2024, p. 88; see also, Morozov, 2013).

This post dives deep into the specifics of the Department of Commerce’s NEPA submission. Subsequent posts will dig into the findings of no significant impact (‘FONSI’) for TSMS, Intel, Micron, and other individual company’s as they become available.

Some Background

Environmental assessments submitted for CHIPS funding use a process under 40 CFR 1501.11 and 1502.4 that allows for the creation of what are called Programmatic Environmental Assessments (PEAs). PEAs can be used by federal agencies to conduct “broad or holistic evaluation of effects or policy alternatives […] or avoid duplicative analysis” (40 CFR 1501.11) where specific individual actions subject to assessment are substantively similar to one another in some way or another (e.g., across a geographical region, by industrial sector, and/or stage of technological development). No additional NEPA review is required if all of the proposed activities under a given PEA are deemed “similar enough to the activities analyzed in the PEA to support a conclusion that their impacts will not be different from those described in the PEA” (United States Department of Commerce and National Institute of Standards and Technology, 2023, page 2).

To date, three companies have submitted draft environmental assessments using PEA requirements as part of their proposals to obtain funding under the CHIPS Act. TSMC was the first to submit such a plan. Public comment on the draft document closed July 12, 2024. Intel and Micron also submitted a PEAs with public comments closing August 6, 2024 and August 8, 2024 respectively. Each of the company’s documents runs hundred of pages long (Micron breaks the pattern by also including an appendix in excess of 2600 pages). I’m going to discuss each of these company’s PEA submissions in later post(s). Here I focus on the Department of Commerce’s [DOC] PEA submission because it sets the table for all subsequent submissions by individual companies seeking funding under the CHIPS program.

The main takeaway from DOC’s submission is its finding of no significant impact [FONSI]. DOC’s PEA covers nine impact categories that I will cover in the order they appear in the document:

Climate Change and Climate Resilience

Air Quality

Water Quality

Human Health and Safety

Hazardous and Toxic Materials

Hazardous Waste and Solid Waste Management

Utilities

Environmental Justice

Socioeconomics

In what follows I’m going to take a critical look at how a FONSI arises in each of these categories, one by one. I am also going to attempt to characterize the types of arguments put forward to justify a FONSI. To preview the latter point I argue that there the FONSI is premised on five types of argument:

1) Misleading comparisons and false equivalencies (see Climate Resilience section and F-GHGs).

2) Recognition and dismissal of known effects (Jevons, see air quality)

3) Scalar mismatch (a misalignment between problem(s) identified and the solutions put forward to solve them) (see Liboiron and Lepawsky, 2022, page 39-46 for deeper discussion of scalar mismatch) (open access pdf here).

4) Faith in regulatory capacity and enforcement.

5) Faith in technological solutionism which presupposes that problems like environmental impacts are discrete, bounded harms that can be fixed with the right technical design of machinery or policy in isolation from the broader systems that give rise to them.

Hopefully, this is more than an academic exercise. Rather than simply criticizing the FONSI for its own sake I am interested in how surfacing the implicit assumptions built into it might offer alternative ways of thinking about impacts and acting to eliminate or mitigate their negative effects.

Making Sense of a FONSI

To unpack DOC’s FONSI, it’s important to understand how ‘scope’ is defined in the Programmatic Environmental Assessment (PEA). According to DOC, a PEA approach is relevant under CHIPS if one or more of the following activities is to be undertaken: replacing existing equipment; upgrading of existing equipment; adding new semiconductor manufacturing equipment; expanding clean room space and adding new clean room equipment; and/or disposing the equipment that is replaced (United States Department of Commerce and National Institute of Standards and Technology, 2023, page 4). It is important to also note that the DOC document states that any of these activities, “must occur within the existing facility footprint to be covered by this PEA. No additional land disturbance would occur.” (United States Department of Commerce and National Institute of Standards and Technology, 2023, p. 11). This criteria for no additional land disturbance beyond the existing facility footprint is important to keep in mind for a couple of reasons. First, companies approved to receive CHIPS funds cannot use those funds to support activities outside their existing footprint; but, second, companies might decide to expand their footprints because they have freed up their own capital resources for expenditures as a consequence of receiving CHIPS funds they can devote to replacing/upgrading activities. Consequently, it is possible that expansion projects that would not have occured without CHIPS funds will, nevertheless, be undertaken yet be outside of NEPA requirements for environmental assessment if CHIPS funding is not directly used to support such expansion. As I will get to in subsequent post(s), there is already evidence of such consequences underway: documents submitted by TSMC, Intel, and Micron point to various degrees of land disturbance beyond extant facilities.

DOC restricts the scope of the PEA by describing the “resource areas” that are considered, but not subject to full analysis (United States Department of Commerce and National Institute of Standards and Technology, 2023, page 18). These areas include: land-use, cultural historic resources, geology, topography, and soil, coastal barrier resources and wild and scenic rivers, wetlands and flood plains, terrestrial biological resources, visual resources, transportation and traffic. The reason DOC excludes these factors from full analysis is that all of the proposed action is assumed to take place “within the existing facility footprint” (United States Department of Commerce and National Institute of Standards and Technology, 2023, page 18). Notwithstanding these factors excluded from full analysis, the draft environmental assessment submitted by TSMC, Intel, and Micron each speak to these excluded factors, in some cases very extensively (i.e., over dozens of pages). In so doing, these companies end up disclosing a great deal of information about their existing and proposed actions beyond the information that they are required to disclose as part of the PEA process under the CHIPS program and its requirements to conform to NEPA legislation. They offer up a considerable amount of quantitative and qualitative data for critical analysis even as their submitted documents are, like any data, partial and situated.

When I say ‘critical analysis’ I have in mind something other than a finger wagging exercise or merely claiming that ‘things could be better’. Instead, I am talking about sifting through these documents to identify their explicit and implicit assumptions that build a semblance of coherence to their claim of providing an ‘environmental assessment’ of semiconductor manufacturing that finds no significant impact from the proposed activities (for a conversational introduction to this approach to critical analysis, see Foucault, 1982). This kind of critical analysis is valuable because implicit and explicit assumptions frame a given issue in particular ways and not others. How an issue is framed matters because it makes certain ways of dealing with the issue seemingly obvious while ruling potential alternatives out of order or even unthinkable altogether. The kind of critical analysis I have in mind is about identifying implicit and explicit assumptions with the purpose of changing how the issue(s) in play may be thought about. The point of articulating such alternatives is to enable what might have remained latent (or not previously thinkable) to be surfaced and, at least potentially, to be acted upon.

What does ‘significant’ mean under NEPA?

‘Significance’ takes on specific meaning under NEPA legislation (see 40 CFR 1501.3(d)). To determine significance, “agencies shall examine both the context of the action and the intensity of the effect” (40 CFR 1501.3(d), see also the ruling made by the Council of Environmental Quality on July 16, 2020 (85 FR 43304).

There are notable differences between the definition of “significance determination” under 40 CFR 1501.3(d) and the DOC’s definition of “significance criteria” in its draft PEA for semiconductor fabrication facilities assessed under the CHIPS program. One example is how “context” is defined. NEPA defines context using geographic characteristics such as area, proximity, and a set of nested scales from “… global, national, regional, and local contexts” (40 CFR 1501.3(d)(1)). DOC, on the other hand, uses the same nested scales, but leaves out ‘global’. NEPA also directs agencies to consider duration of effects without specifying what that means beyond “short- and long-term” (40 CFR 1501.3(d)(1). Meanwhile, DOC lists temporary, short-term, long-term, and permanent effects. The DOC’s temporal definitions depend on whether the effects would only occur during the active construction of a fab [‘temporary’] or would last indefinitely [‘permanent’] “for the life of a semiconductor fabrication facility” (United States Department of Commerce and National Institute of Standards and Technology, 2023, page 20).

Quite apart from the differences between the NEPA legislation and DOC’s draft PEA, there are some obvious questions that arise from these otherwise seemingly basic distinctions related to spatial and temporal categories. For example, questions about the meaningfulness of temporal categories like temporary and permanent. When permanence is defined as “the life of a semiconductor fabrication facility”, the quantum of time presupposed might be a matter of decades, say 20 or 30 years. On the other hand, some of the chemicals involved in semiconductor manufacturing, even when used in very small quantities, do not break down on time scales that are meaningful for human lives – – rather than years or decades, it’s centuries or millennia that are relevant for things like PFAS (aka ‘forever chemicals’). My point here is not that defining ‘permanent’ as the ‘life of a semiconductor fabrication facility’ is wrong per se. Instead my point is that this definition is arbitrary, partial, and situated. It is going to be a point of debate for publics (plural) that cohere around their (variable and conflicting) interests in the projects described in these PEA documents. And, because of the arbitrary, partial, and situated character of the meaning of these temporal categories (and others, see below), there will be no way to non-arbitrarily close the debate. The absence of an ability to non-arbitrarily close debate means they will be ‘political’,

As philosopher and STS scholar Annemarie Mol notes, “[I]t may help to call ‘what to do?’ a political question. The term politics resonates openness, indeterminacy. It helps to underline that the question ‘what to do’ can be closed neither by facts nor arguments.” (Mol, 2002, page 177 emphasis in the original). Many of the publics that are involved in the debates over the impacts of semiconductor manufacturing will attempt to invoke ‘science’ as an arbiter of what are ultimately political questions – – that is, questions pertaining to the struggle over differential power relations. This is a role that science is poorly formatted play, as Brian Wynne (Wynne, 1987) and others have argued. Why so? Here’s just one quick example from Brian Wynne’s book on managing risks posed by hazardous waste: the US and the UK both regulate the amount of PCBs that can be disposed of in landfills because these chemicals are known to be harmful to biological systems (like human bodies). However, the regulations on PCBs in the two jurisdictions differ by a factor of five. Toxicological science can tell you about harms from PCBs, but it can’t decide which of the two jurisdiction’s regulations are ‘right’ and, thus, tell policymakers or other publics what to do.

DOC’s draft PEA for the CHIPS Act also attempt to adhere to the NEPA requirement to consider the intensity or severity of the impacts by offering four qualitative impact categories:

1) Negligible: “Minimal impact on the resource would occur; any change that might occur would be barely perceptible and would not be easily measurable.” (United States Department of Commerce and National Institute of Standards and Technology, 2023, p. 27).

2) Minor: “Change in a resource would occur, but no substantial resource impact would result; the change in the resource would be detectable but would not alter the condition or appearance of the resource.” (United States Department of Commerce and National Institute of Standards and Technology, 2023, p. 27).

3) Moderate: “Noticeable change in a resource would occur and this change would alter the condition or appearance of the resource; the integrity of the resource would remain intact.” (United States Department of Commerce and National Institute of Standards and Technology, 2023, p. 27).

4) Major: “Substantial impact or change in a resource would occur that is easily defined and highly noticeable and that measurably alters the condition or appearance of the resource; the integrity of the resource may not remain intact.” (United States Department of Commerce and National Institute of Standards and Technology, 2023, p. 27).

The impact categories above immediately raise questions about perceptibility and measurability and what to do about this or that impact of a given category. One might want to ask, for example, perceptible and measureable to whom and/or to what? How, where, when, and under what conditions? Answers to these questions are going to be political in the sense of struggles pertaining to uneven power relations.

Also, although there is nothing explicit in the DOC definition of impact, there is, at the very least, a latent anthropocentric element to these definitions. Who is the ’anthropos’ or ‘human’ implicitly invoked in these impact categories? Both NEPA and DOC do offer a partial answer that question. The answer includes the need to consider “environmental justice” as defined by the US EPA and as reaffirmed and defined in Executive Order (EO) 14096 issued on April 21, 2023. Here, environmental justice means,

the just treatment and meaningful involvement of all people, regardless of income, race, color, national origin, Tribal affiliation, or disability, in agency decision-making and other Federal activities that affect human health and the environment so that people (EO 14096 Sec. 2 (b)):

are fully protected from disproportionate and adverse human health and environmental effects (including risks) and hazards, including those related to climate change, the cumulative impacts of environmental and other burdens, and the legacy of racism or other structural or systemic barriers; and (EO 14096 Sec. 2(b)(i))

have equitable access to a healthy, sustainable, and resilient environment in which to live, play, work, learn, grow, worship, and engage in cultural and subsistence practices (EO 14096 Sec. 2(b)(ii)).

Liboiron et al., (Liboiron et al., 2023) offer some helpful ways to understand both the implicit and explicit models of justice in play in the EO 14096 definition of environmental justice and its incorporation into DOC’s draft PEA for the semiconductor manufacturing industry.

There are two explicit models of justice in the EO 14096 definition of environmental justice cited above: procedural justice and distributive justice. Procedural justice refers to concerns about equity of ability to participate in decision making processes (e.g., public meetings; public comment on regulations and the like). A model of procedural justice is evidenced where the EO 14096 definition refers to “meaningful involvement of all people, regardless of income, race, color, national origin, Tribal affiliation, or disability in agency decision-making”. For example, to be ‘meaningful’, people should have the ability to participate in public meetings that are scheduled at a time and place reasonably accessible to them, rather than having to take time off from work to attend.

Liboiron et al., (Liboiron et al., 2023) describe distributive justice as a concern about uneven harms experienced by people and places based on social distinctions such as race, class, gender, and/or age. There are important differences of orientation toward distributional justice Liboiron et al., (Liboiron et al., 2023 citing Ewall) clarify as the difference between seeking to poison people equally versus stopping poisoning people altogether. Another important difference of orientation to distributional justice is orienting concern toward discriminatory systems as sources or causes of harms (e.g., capitalism, racism) rather than toward characteristics of individual people (e.g., poor, working-class, Black, white, etc) as inherently being risk factors for being on the receiving end of harms. The EO 14096 definition of environmental justice is ambiguous on these different orientations toward distributional justice. For example, ensuring that people “are fully protected from disproportionate and adverse human health and environmental effects” could be interpreted to mean both ‘poison people equally’ and to mean ‘stop poisoning people all together’.

There is also an important model of justice that is latent in the NEPA legislation and the DOC’s draft PEA for semiconductor manufacturing. This model of justice is what Liboiron et al., (Liboiron et al., 2023) call developmental justice. A developmental justice model takes it as right and good that Industry and its underlying economic systems are able to “endure, grow, and flourish (develop) without significant interruption or hardship” (Liboiron et al., 2023, page 6). Such a developmental justice model is largely, though not completely, an unstated assumption of the DOC’s draft environmental assessment PEA (and those submitted by companies seeking funding into the CHIPS program). Where a developmental justice model is most explicit is in the requirement of NEPA–based environmental assessments to consider socioeconomic effects and the insistence in the DOC’s draft PEA that such effects only manifest as benefits (e.g., employment creation). Yet, decades-old socioeconomic analyses from Silicon Valley (Bernstein et al., 1977; United States Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2009) and the broader US tech-sector suggest such sanguine assessments are misguided (see also ‘Layoffs.fyi’).

I am now going to turn to each of the nine impact categories covered by the DOC’s NEPA submissions, starting with ‘Climate Change and Climate Resilience’.

Climate Change and Climate Resilience

There are interesting and consequential things going on with greenhouse gases (GHGs) and semiconductor manufacturing disclosed in the DOC PEA. For example, DOC claims the sector is indirectly responsible for 5.3 MMT CO2e of GHGs from fossil fuel-based energy production (United States Department of Commerce and National Institute of Standards and Technology, 2023, p. 34). Meanwhile, manufacturing processes in semiconductor manufacturing account for roughly equal amounts of GHGs at 5.42 MMT CO2e. On the surface, these two figures of 5.3 and 5.42 MMT CO2e might seem basically similar. They are not.

Fossil fuel based GHG emissions for energy production can, at least in principle, be substituted via transition to renewable energy sources (e.g., solar, wind). Substituting the GHGs from the manufacturing process, however, is a radically different proposition for several reasons. The majority of manufacturing process GHGs are fluorinated (F-GHGs) (84 percent; carbon dioxide and nitrous oxide make up the remaining 12 and 4 percent respectively). Unlike with energy generation where renewables can substitute for fossil fuel sources, there are no substitutes for all F-GHGs in semiconductor manufacturing.

Although the EPA notes,”fluorinated GHG emissions from semiconductor manufacturing can be reduced”, reduction is not elimination. A recent report from the Semiconductor Industry Association (a trade group) concurs: “[c]urrently, there is no known substitute for fluorocarbon gases” (Semiconductor PFAS Consortium Plasma Etch and Deposition Working Group, 2023, p. 10).

F-GHGs are hundreds to tens-of-thousands of times more potent greenhouse gases than carbon dioxide (see “Table 3.4-1. 100-Year Global Warming Potential of Select Greenhouse Gases” (United States Department of Commerce and National Institute of Standards and Technology, 2023, p. 35). That means even when used in small amounts, they can have large magnitude global warming consequences. So, while one large chunk of GHG’s from the industry–those related to energy production–may be able to be mitigated or eliminated, another chunk of basically the same magnitude–F-GHGs in manufacturing–will be much more difficult, even impossible, to mitigate or eliminate because there are no substitutes (maybe there will be in the future, but at this point that is speculation).

DOC’s PEA claims that semiconductor manufacturers have found ways to abate GHGs, including F-GHGs. But DOC’s own report suggests reasons to be concerned. For example, of 51 semiconductor fabrication facilities considered in DOC’s report, 27 (>50 percent) reported using no GHG abatement systems at all (United States Department of Commerce and National Institute of Standards and Technology, 2023, p. 36). Where such systems are used DOC claims that they have removal or destruction efficiency of up to 70%. Yet, because of the very substantial global warming potential of F-GHGs even high efficiency for removal or destruction can still have large magnitude facts on global warming. Look back at Table 3.4-1. Removing or destroying 70 percent of 1 ton of sulphur hexafluoride (SF6) is equivalent to releasing 6,840 tons of CO2.

In spite of such stark realities, DOC’s draft PEA claims that the effects of both the no action- and the proposed action alternatives will have basically the same qualitative impact on the climate emergency. The no action alternative “would continue to be a negligible to minor, adverse, long-term, global effect on GHG emissions and resultant climate change and climate resiliency.” (United States Department of Commerce and National Institute of Standards and Technology, 2023, page 28). Whereas, the proposed action alternative “would have a negligible to minor, long-term, global effect on climate change from GHG emissions” (United States Department of Commerce and National Institute of Standards and Technology, 2023, page 29). Apparently, the only difference between the two scenarios is the word “adverse”.

It appears as though the DOC is willing to say that proposed projects will affect global climate, but unwilling to characterize those effects as negative. How does the organization arrive at such an assessment? The answer is: by comparing the climate consequences of individual semiconductor manufacturing facilities to the total emissions from the entire semiconductor manufacturing sector and to the total emissions of the entire United States!

the marginal increase in GHG emissions from an individual modernization project would be negligible compared to overall U.S. emissions and emissions from the semiconductor industry sector (United States Department of Commerce and National Institute of Standards and Technology, 2023, page 29).

This appeal to ‘marginal increase’ is misleading. It should be no surprise to learn that if you compare the GHG emissions of a single semiconductor fabrication plant to the emissions from the entire sector or, indeed, the emissions of the United States as a whole, then of course one would conclude with a finding of no significant impact [FONSI]. It’s a fallacy of magnitude to assess the effects of a single industrial facility by comparing it to the entire economic sector of which that facility is a part, let alone to the national level of the country where the facility is located. Such a justification is a form of false equivalence (I mean, hey, didn’t you know? Adding each individual additional car to a crowded highway has a negligible effect when thousands of cars are already jamming the roadway).

Air Quality

“Proposed Action would be direct and long term and localized to regional because of increases in air emissions resulting from increased production. These effects would be adverse and negligible when compared to current conditions, but they could be beneficial and minor if new air pollution control measures and best available control technologies were introduced with the modernization to reduce the overall pollutant load in air emissions from facility operations.” (United States Department of Commerce and National Institute of Standards and Technology, 2023, p. 43).

In the quote above, DOC implicitly recognizes the Jevons paradox or rebound effect. Let’s say new air pollution control measures reduce that pollution by 10% but production of new semiconductors increases 10%. If that happens, then the net change in air pollution is zero. If semiconductor production rises above the 10% improvement in air pollution, then total air pollution increases.

That DOC recognizes the rebound effect makes the conclusion of a FONSI at least open to question. At best, DOC’s PEA waves the rebound effect away without actually dealing with it in substantive ways.

Water Quality

DOC characterizes the environmental impacts associated with water quality as a FONSI because facilities would still have to meet compliance requirements under their existing waste water discharge permits. Meanwhile, the DOC also characterizes wastewater effects as “direct, long-term, localized to regional effects on water quality; these effects would be adverse and minor compared to current conditions. If the proposed action included new measures to reduce the pollutant load in the wastewater there could potentially be beneficial and minor effects.” (United States Department of Commerce and National Institute of Standards and Technology, 2023, page 42). Consequently, the DOC’s assessment of effects on water quality are mixed. They span a range from minor adverse consequences to minor beneficial effects.

Some of DOC’s mixed range of results arise from the plethora of different chemicals used in semiconductor manufacturing. Some of the chemicals used are relatively benign and/or can be easily treated so as to mitigate or eliminate their toxic consequences. Other classes of chemicals, however, are problematic because they are difficult or impossible to treat and/or their toxicological pathways and effects are poorly understood. This indeterminate situation is well illustrated via the use of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs).

The uses of PFASs in semiconductor manufacturing are multiple and complex. Both industry and environmental NGO (ENGO) reports agree that there are no alternatives for some uses of PFASs in at least some phases of semiconductor manufacturing. The Semiconductor Industry Association (SIA) has produced a large number of technical reports and white papers on the uses of PFASs in semiconductor manufacturing. These reports go into substantive technical detail and make the case that contemporary semiconductor manufacturing is not possible without PFASs. ChemSec, a Swedish ENGO dedicated to the reduction and elimination of the use of hazardous chemicals, arrives at the same conclusion: there is a lack of alternatives to PFAS use in some phases of semiconductor manufacturing (Lay et al.). Whereas SIA’s position is categorical–there are no alternatives to PFAS in most instances–ChemSec is more circumspect noting that in multiple phases of semiconductor manufacturing, “[a]lternatives do not seem to be available” (Lay et al., p. 20). Although the positions of SIA and ChemSec differ on the technical difficulties of finding and implementing a PFAS alternatives, there is no question that they agree on the absence of such alternatives in specific phases of semiconductor manufacturing.

Regardless of the differences in tone between SIA and ChemSec, finding alternatives to PFASs in semiconductor manufacturing is a genuinely challenging technical problem due to the physical characteristics of contemporary semiconductors. There are many nuances and complexities here, but one good example of such challenges come from the use of PFASs in wet chemistry processes used during the manufacture of semiconductors.

Semiconductor structures, such as transistor gates, are etched onto semiconductor surfaces. Those structures are now created at magnitudes of between 1 and 10 nm, or roughly the size of DNA (see, Jones and RINA Tech UK Limited (RINA), 2023, page 23). These small sizes make semiconductor structures susceptible to something called “pattern collapse caused by capillary forces” (Semiconductor PFAS Consortium Wet Chemicals Working Group, 2023, p. 15). This kind of pattern collapse happens when the surface tension of fluids used to etch structures into semiconductors generate enough force to bend or warp those structures. Such bending or warping leads to physical flaws in the resulting semiconductor (i.e., ‘pattern collapse’). Some PFASs are extremely good at reducing the surface tension of fluids, thus reducing the forces associated with capillary action, and thus reducing or eliminating the chances of pattern collapse. This is an example of the use of PFASs for which alternatives have yet to be found and manufacturing such small semiconductor structures would not be possible without those PFASs.

Noting this example of PFAS use to avoid pattern collapse points to the issue of determining ‘essential use’, a key point of contention between diverse actors of industry, toxicology, and environmental advocates. No doubt there are those who would point to devices like smart phones and ask whether such things are really essential. A debate could be had about that, but depending on one’s situation the ability to do every day things that are part of coordinating work and nonwork tasks or accessing government services are increasingly dependent on devices like smart phones. More importantly, thinking about what is or isn’t an ‘essential use’ needs to grapple with the very wide integration of semiconductors into whole swaths of applications well beyond personal electronic/consumer devices. Consumer electronics make up less than 7% of semiconductor end markets by revenue (Jones and RINA Tech UK Limited (RINA), 2023, page 17). In this respect, consumer electronics are a bit like postconsumer waste in discard studies: ‘we’ think we know electronics because ‘we’ handle our phones or devices. Yet, >93% of the end market for semiconductors is composed of non-consumer electronics at work elsewhere in the sociotechinical coordination of the collectives in which ‘we’ persist.

Lack of alternatives to PFAS and debates over essential use are just part of the picture. Between 2014 and 2018, toxicologists published a series of statements describing concerns about PFASs held by practitioners in the field after major international conferences held in Helsingør, Madrid, and Zürich.

The Helsingør Statement addresses the transition in the industrial use of PFAS from long-chain to short-chain alternatives. The difference between long-chain and short-chain PFASs is how many fluorine and carbon atoms are bonded in the compound. Long-chain PFASs are those with more than six such bonds (Scheringer et al., 2014).The authors of the Helsingør Statement sought to “summarize key concerns about the potential impacts of fluorinated [short-chain] alternatives” (Scheringer et al., 2014, page 337). These authors write that “PFASs have been found to be persistent, bioaccumulative and toxic” (Scheringer et al., 2014, p. 337), suggesting that scientific knowledge about the toxicity and associated characteristics of these chemicals was settled by 2014. That PFAS manufacturers were transitioning to short-chain alternatives at the time is further acknowledgement that the problematic nature of long-chain PFAS were already established.

Key concerns according to the authors of the Helsingør Statement include:

-There is little information in the public domain about, “production volumes, uses, properties and biological effects” (Scheringer et al., 2014, p. 337) of short-chain PFAS.

-Nevertheless, short-chain PFAS had already been demonstrated to be persistent in the environment similar to their long-chain predecessors.

-Such similar persistence points to risks of bioaccumulation and toxicity of short-chain PFASs that are the same or similar to their long-chain cousins. Consequently, short-chain PFAS may not offer any substantive improvement over the long chain compounds they replace.

-Although short chain alternatives are being manufactured and put into industrial uses, long-chain PFASs also continue to be manufactured and used (albeit at declining rates for some of those long-chain compounds). Thus, the transition to short chain alternatives risks leading to aggregate increases in the total volume of PFASs in circulation. In other words, rather than the alternatives leading to an overall decline in PFAS production and use, they are leading to an aggregate increase in PFASs accumulating in the environment. If so, this aggregate increase would be an example of the rebound effect at work in the chemical realm.

Two major recommendations are articulated in the Helsingør Statement:

1) Chemical manufacturers should be required (i.e., regulated) to make their toxicological data public since it is public money that is used to produce the toxicological data about the effects of the industry’s products on human and environmental health and to clean up the industry’s externalities (recent research by Ling, 2024, page 1 shows such clean-up to be impossible to an absurd degree. Such clean up “would cost more than global GDP.”).

2) Research, development, and production of non-persistent alternatives to PFAS should be pursued and, “PFASs should only be used in applications where they are truly needed and proven indispensable.” (Scheringer et al., 2014, p. 339). The authors do not articulate how such proof of indispensability can or should be determined. This issue of need and indispensability will become a key plank for industry counter arguments about the need for regulation of PFASs and their alternatives.

In 2015, the Madrid Statement was published by another group of scientists, some of whom had co-authored the Helsingør Statement the year before. Madrid summarizes the Helsingør Statement and re-emphasizes the concerns over PFASs arising from their persistence, ubiquity, their propensity for bioaccumulation, and their toxicity. The authors of Madrid then go on to address a number of recommendations to six audiences: scientists, governments, chemical and product manufacturers, purchasing organizations, retailers, and consumers. Among other things, the authors urge scientists, governments, and chemical manufacturers to make data on PFASs public. Such data should include chemical structures, properties and toxicology. The Madrid statement also urges manufacturers to stop using PFASs, “where they are not essential or when safer alternatives exist” (Blum et al., 2015, p. 108); and encourage manufactures to label products that contain PFASs so that purchasing organizations, retailers and individual consumers can, “wherever possible” avoid products containing PFASs (Blum et al., 2015, p. 108).

The Madrid Statement provoked a counter response from the FluoroCouncil, an industry lobbying and public relations suborganization of the American Chemistry Council, published in the same journal later in 2015. The main claim of the counter response is that fluouro chemistry, of which PFASs are members, “uniquely enhances the functionality and durability of things we take for granted, such as airplanes, automobiles, and cell phones” (Bowman, 2015, p. A 112) and are thus “critical to modern life” (Bowman, 2015, page A112). One might immediately ask “we” who? Where? When? And under what conditions? A set of questions that also bear on the Madrid Statement itself where it encourages consumers to choose to avoid products with PFASs. Given the ubiquity of these chemicals what can ‘choice’ really mean and for whom, where, when, and under what conditions?

More tellingly, the FluoroCouncil’s response notes that “[d]ata in non-human primates indicate shorter-chain perfluoroalkyl carboxylic acids (PFCAs) are less toxic than long-chain PFCAs” (Bowman, 2015, p. A 112) Note “less toxic”. Less toxic is not non-toxic. So even the industry’s advocate, the FluoroCouncil, is admitting that short-chain PFAS alternatives, although ‘better’ than long-chain ones, are still toxic. Meanwhile, the organization claims that criticisms of PFASs are based on a single feature of them, that is, their persistence. The Madrid Statement (and Helsingør Statement before it) do, indeed, note persistence as a problematic characteristic of PFASs. But the counterclaim that persistence is the only the characteristic that these criticisms are based on is disingenuous. Both Helsingør and Madrid also include ubiquity, bioaccumulation, and toxicity among the problematic characteristics of this class of chemicals.

To address the criticisms levelled against PFASs the FluoroCouncil advocates for status quo risk assessment research to guide, “[a]ny assessment of the alternatives to long-chain PFASs” (Bowman, 2015, p. A 112) and that the transition to short-chain alternatives, “should be the centerpiece of policy on PFASs” (Bowman, 2015, p. A 113). In these ways, the FluoroCouncil contemplates only aggregate growth in the use of PFASs albeit in the form of short-chain compounds. Neither aggregate reduction, nor elimination are permitted to enter the range of possible alternatives for consideration. Ultimately, the FluoroCouncil’s counter response is about bolstering a claim for developmental justice i.e., that it as right and good that industry and its underlying economic systems can flourish (Liboiron et al., 2023).

Authors of the Madrid Statement produced their own rebuttal to the FluoroCouncil’s claims. Among their counterpoints, the authors note that research commissioned by the FluoroCouncil itself, “identified many gaps regarding human health data” (Cousins et al., 2015, p. A 170) and that such gaps prohibit assessments of the hazards and risks associated with fluorinated chemicals such as PFASs. In contrast to status quo developmental justice, the authors of this rebuttal advocate for green chemistry, especially “design for degradation” (Cousins et al., 2015, p. A 170) whereby chemical products breakdown into benign substances once they reach the end of their functional lives. In this respect, the authors are engaged in alternatives assessment rather than risk assessment (O’Brien, 1993). Instead of research based on finding a a level of harm below which is acceptable and above which is unacceptable, these authors are advocating for the elimination of harm in the first place through principles of green chemistry.

The FluoroCouncil felt compelled to respond to this rebuttal. The organization remained “perplexed by assertions from the authors of the Madrid Statement that short-chain PFASs present hazards comparable to those of long-chain PFASs” (Bowman, 2015, page A171) and faulted the Madrid Statement authors for not citing what the FluoroCouncil considers a key study on the toxicity of short-chain PFASs. The study in question is Klaunig et al. (Klaunig et al., 2015). The study is worth unpacking a bit.

It is true, per the FlouroCouncil’s claim that Klaunig et al. (Klaunig et al., 2015) found no carcinogenic effects in rats exposed to a short-chain PFAS. The FlouroCouncil fails to note, however, that the study did find statistically significant decreases in survival rates between male and female rats treated at different doses. What Klaunig and colleagues (Klaunig et al., 2015; see also, Peters and Gonzalez, 2011) actually found was that as doses doeses of PFAS increased in male rats, survival also increased, but in female rats–who were dosed at double the volume of male rats–survival declined as doses increased.

There is a lot going on here in terms of the gendered dynamics of technoscience, the instrumentalization of non-human lives, biopower, and necropolitics–but I’m just going to make a relatively small point which is this: the FluroCouncil’s own preferred study shows a definite harmful toxicological response to doses of one short-chain PFAS disproportionately experienced by female rats. Sure, none of the rats got cancer but as doses increased, the survival of female rats declined from 43% to 22% (i.e., 78% were killed by the highest dose; see Table 3 ‘Survival of male and female rats after PFHxA treatment.’ Klaunig et al., 2015, page 213). This finding enables the FluoroCouncil to claim that, “short-chain PFASs are less bioaccumulative and less toxic than the long-chain PFASs” (Bowman, 2015, page A171). The FluoroCouncil goes on to assert that, “[b]ecause the short-chain PFASs have been reviewed and approved by regulatory authorities globally, all applications relying on these substances can be used without presenting a significant risk.” (Bowman, 2015, page A171)–a logically absurd conclusion given past regulatory scandals (e.g., thalidomide).

Following the Madrid exchanges, scientists from 31 different organizations across Europe, North America, and Asia published the Zürich Statement on Future Actions on Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs) (Ritscher et al., 2018). Zürich reports the key points from a two day workshop held in November 2017 with international scientists and regulators concerned about PFASs. Like its predecessors, Zürich emphasizes PFASs persistence, ubiquity, and toxicity as sources of deep concern for environmental toxicology. The statement offers a number of recommendations for coordinated work between scientists and policymakers to mitigate the hazards of PFASs.

First among these recommendations is a need for coordination between scientists and policymakers. The authors note for example that neither scientific nor policy discussions of PFASs use consistent terms or identifiers for these substances. This makes it difficult to track emerging hazards and the effectiveness of regulation. The creation of a centralized repository of standardized PFAS terms and definitions is one suggestion offered. In this respect, PFAS discussions represent a substantial site for research for STS scholars interested in questions of the work and effects that categorization and standardization do to stabilize different forms of scientific knowledge and power (e.g., Bowker and Leigh-Star, 1999; Yates and Murphy, 2019).

It’s also notable that the authors of the Zürich Statement see a need for standardization since to see that need implies that there is a degree of uncertainty, perhaps even indeterminacy, about what chemical compounds actually count as PFASs. In other words, there may be disagreement among scientific and policy experts themselves regarding basic ontological and practical questions about PFASs (i.e., What counts as a PFAS? What is an ‘essential use’ of them?). As such, PFAS science and policy-making are likely to be good sites for STS oriented controversy mapping research that traces how and why technical scientific and policy disagreements are (or are not) settled and come to gel into social arrangements (e.g., Venturini, 2010; Venturini and Munk, 2021). Notably the authors of the Zürich Statement head off the use of uncertainty as a tool for, “postponing cost-effective measures to prevent environmental degradation” (Ritscher et al., 2018, p. 3). Researchers such as Oreskes and Conway (Oreskes and Conway, 2010) have shown how uncertainty is weaponized by anti-regulationist interests to put off changes to status quo industrialism to an ever receding horizon of the future.

Even as Zürich invokes the precautionary principle, it does so within the brackets of ‘cost effective measures’, suggesting the authors of Zürich accept a limit on precautions against harms of PFASs defined by costs such precaution could have. There is, in other words, at least a latent acceptance of developmental justice i.e., permitting industry to flourish without undue imposition of costs to it.

Participants at the Zürich conference, “widely agreed that socioeconomic analyses on the uses of PFASs and their alternatives need to be conducted, and some participants further voiced that such socioeconomic analyses need to reflect the long-term societal costs associated with the very high persistence of many PFASs.” (Ritscher et al., 2018, p. 3). Analyzing the kinds of taken for granted assumptions and the opportunities suggested by STS research on categories and controversies could substantively contribute to this need for “socioeconomic analyses” recognized by the Zürich authors themselves. Such socioeconomic research could also contribute toward fostering transitions to safe(r) alternatives to PFASs (in general and/or in specific sectors or use cases). In other words, what might be a viable path to alternatives in fire fighting foams, may or may not be viable in semiconductor manufacturing. The latter are just two products/industries in which PFASs of different kinds are widely used. But what constitutes an alternative in one use case may not do so in another and, consequently, what counts as ‘essential use’–a key area of disagreement according to the authors of Zürich (Ritscher et al., 2018, page 3)–is likely to be highly variable and contested. Figuring out how agreements could be reached to overcome such contestation between different actants and their interests could be a major contribution of STS research in this area. If further evidence of potential contributions of STS scholarship are needed, the authors of Zürich note that while, “[t]here was unanimous agreement among the participants that to adequately address PFASs, a strong science-policy interface is required. However, participants from the scientific community noted that needs of the regulatory community are often not obvious for the scientific community and may also differ considerably across regulatory frameworks” (Ritscher et al., 2018, p. 4). On this point about the science–policy interface work by Wynne and Boudia and Jas will be key touchstones (Wynne, 1987; “Powerless science? science and politics in a toxic world”, 2014).

Meanwhile, DOC’s environmental assessment frames discussions of regulatory control of wastewater from the sector using 40 CFR Part 469 which presupposes a monotonic threshold model of harm (e.g., milligrams of pollutant X per litre of water or mg/l; see Figure A below; see also: United States Environmental Protection Agency, 2022). In the US, the underlying assumptions of a monotonic threshold theory of harm derive from foundational work by two engineers, Phelps and Streeter, and their early 20th century studies on organic contamination of rivers in Ohio (Liboiron, 2021). A monotonic threshold theory of harm can work for some toxicants, but for others–like PFASs–they do not match toxicological behaviours where there is knowledge of them.

It is clear that harms associated with PFASs vary wildly. The variation can depend on the length of the molecule and the functional group of PFAS that is being considered. There’s also wide variation based on species and sex differences in the animal models studied (“Toxicological Effects of Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances”, 2015, p. 6). Toxicological curves for PFASs appear to include the gamut like those relevant to carcinogens (i.e., linear non-thresholds, where harm occurs on contact, see Figure B above) and those associated with endocrine disruptors (simple and complex nonmonotonic curves, see Figure C and D; some PFASs may act as endocrine disruptors themselves, but they also exhibit nonmonotonic curves that are about toxic responses other than endorine disruption per se).

Such a mismatch between the toxicological behaviour of a family of chemicals, such as PFASs, and the underlying theory of harm on which regulations are based is a problem. The field of discard studies has developed the concept of ‘scalar mismatch’ to describe a misalignment between a problem, such as chemical harms or pollution, and the solutions put forward that will ostensibly mitigate or eliminate that problem.

Arguably, the DOC’s environmental assessment can arrive at finding of no significant impact (FONSI) for water quality and PFASs for three reasons that work in combination with one another. First, the underlying theory of harm is misaligned with the toxicological behaviour of the PFASs that toxicologists have at least some knowledge of. Second, there are very significant blank spots on the map of PFAS toxicology, as the Helsingør, Madrid, and Zürich statements all emphasize. Third, the proposed action contemplated by DOC (expanding or building new semiconductor manufacturing capacity) will include various forms of wastewater treatment. In combination, these three factors enable DOC to state that the proposed action, “could result in fewer toxic compounds in wastewater, resulting in minor, beneficial effects.” (United States Department of Commerce and National Institute of Standards and Technology, 2023, page 41, emphasis added). DOC’s assessment under these conditions is techno-solutionist in orientation and seems optimistically speculative, at best.

Is there another way that DOC’s environmental assessment of PFASs and other chemical toxicants could proceed? One alternative is to offer an assessment based on violence, rather than harm. Liboiron (Liboiron, 2021, page 85) argues that harm proceeds from questions like, ‘How much is too much?’. In contrast, concerns about mitigating or eliminating violence proceed from questions like, ‘ How and why are hurt, damage, or adverse effects occurring in the first place?’. Harm type questions might be OK when you’re talking about how much poop is in a river (Streeter and Phelps), but PFASs (and other families of synthetic chemicals) don’t (only) behave like poop. At least some of them cause hurt or damage on contact (e.g., chemicals with linear non-threshold curves such as carcinogens), while others appear to cause harm along nonliner trajectories (e.g., Figure C and D above).

Sidenote: toxicologists suspect some PFASs do act as endocrine disruptors (see Table 1 in DeWitt et al., 2024, page 788). Meanwhile, critical scholars of sex and sexuality contest the automatic linking of harm with non-heteronormative sex and sexuality that may be, at least partially, a result of changes in endocrine systems induced by synthetic chemicals (O’Laughlin, 2020). Notwithstanding those debates, it is important to understand that what is known about the toxicologies of PFASs suggests that at least some of them have nonmontonic toxicological effects, even if those effects are not about changing how endocrine systems function.

Human Health and Safety

A finding of no significant impact (FONSI) for human health and safety is premised on Bureau of Labor Statistics data showing a continual decline of non-fatal occupational injuries and illnesses per 100 workers in the semiconductor and related device manufacturing sector (see Figure 3.7-2 in United States Department of Commerce and National Institute of Standards and Technology, 2023, page 45). DOC’s reasoning indicates confidence in Occupational Health and Safety Administration (OSHA) regulation and voluntary industry standards to maintain or improve declining injury rates even as semiconductor production increases under the CHIPS program. DOC directly acknowledges the role of public activism and lawsuits as key factors that have enhanced occupational safety and health in the industry over the few decades.

Regulatory enforcement, including sufficient enforcement resources such as the number of available inspectors, is one obvious unstated assumption of DOC’s of FONSI for human health and safety. Given the political economic climate of the US, such an assumption may or may not be warranted as attacks on regulatory infrastructure are fostered by some policymakers and judiciaries (e.g., the recent US Supreme Court overturning of the ‘Chevron Defense’).

Hazardous and Toxic Materials

DOC acknowledges that the industry is actively pursuing less or non-toxic alternatives, but that no such alternatives for some problematic materials currently exist. DOC also acknowledges that the quantity of hazardous and toxic materials will increase in proportion to increased semiconductor production. DOC claims that because the proposed actions under CHIPS funding all entail equipment modernization that those changes will lead to improvements in the handling of hazardous and toxic materials, even as the aggregate amount in use increases.

Thus, DOC’s FONSI for hazardous for hazardous and toxic materials is premised on historical trends reducing the risks associated with such materials in the industry continuing as equipment and manufacturing processes are modernized and upgraded. The FONSI simultaneously waves away the problem of the rebound effect (Jevons Paradox)–the problem of increasing aggregate use of hazardous and toxic materials even as gains in effiency of use are acheived.

Hazardous Waste and Solid Waste Management

DOC’s assessment of FONSI for hazardous waste and solid waste management are promised on similar assumptions as those for hazardous and toxic materials. Essentially, the assumption is that equipment and manufacturing process modernization will lead to improvements over the status quo then it is warranted to arrive at a FONSI, even the likelihood that volumes of hazardous and solid waste will increase with increased production. In this respect DOC is, at least implicitly, acknowledging the rebound effect (Jevons Paradox) while simultaneously assuming that those consequences will be negligible relative to the status quo.

Utilities – Water

DOC arrives at a FONSI for water use by semiconductor fabrication facilities by speculating about future improvements from industry wide water recycling rates in 2022 of “between 40 to 70 percent” ” (United States Department of Commerce and National Institute of Standards and Technology, 2023, page 65). DOC claims that technological improvements can, “potentially improv[e] water recycling up to 98 percent” (United States Department of Commerce and National Institute of Standards and Technology, 2023, page 65), but it does so by citing industry journalism (Johnson, 2022) that itself is based on marketing claims by a firm that provides water recycling infrastructure to the semiconductor sector. Such citational politics (Rekdal, 2014) should at least suggest a reason not to simply take DOC’s findings on water use at face value.

Although the technology for recycling water with such high rates of efficiency do exist, there are important assumptions built into DOC’s FONSI for water use. One important assumption is that the new, more efficient water recycling infrastructure can be retrofitted into existing manufacturing facilities. Another assumption is that even if such integration is possible, that semiconductor manufacturers will choose to spend the money to make those improvements. Neither the first nor the second assumption are guaranteed. Thus, while the high-efficiency water recycling technologies that now exist may be integrated into new facilities, that are as yet unbuilt, there is no guarantee they will be incorporated into existing facilities.

A third important assumption is that the impressively high water recycling rates now possible using newer technologies (98 percent) will lead to sufficient declines in aggregate water use such that new demand for water resulting from CHIPS funding will have no significant impact. 98% efficiency is, indeed, an impressive number, but it does not mean zero loss of water. Two percent loss of water per operational day means that every 50 days of operations a facility will have used 100% ‘new’ water. Certainly, this is an improvement over the water requirements recycled at rates of 40 to 70 percent, but whether such improvements are genuinely insignificant would depend on a number of locally relevant social, economic, and environmental factors. Moreover, aggregate water requirements for semiconductor manufacturing operations can nevertheless remain substantial given the magnitude of water requirements even with highly efficient water recycling rates (e.g., 98 percent).

DOC citing Johnson (Johnson, 2022), claims that a semiconductor fab can require up to 10,000,000 gallons of water per day (a bit more than 15 Olympic-sized swimming pools). Daily water requirements are reduced to 200,000 gallons with a 98 percent recycling rate (about 1/3 of an Olympic-sized pool). A 98 percent reduction in daily water needs is impressive indeed, but it is not a reduction to zero. 1/3 of an Olympic sized swimming pool may not be much in the rainy Pacific Northwest, but the issue is entirely different in the desert southwest where drought conditions have prevailed since 1994 (Arizona Department of Water Resources).

Environmental Justice

The DOC’s PEA addresses environmental justice (EJ) in fairly generic terms. Partly this is out of necessity since the legal requirements for EJ considerations under NEPA recommend defining a geographic unit of analysis specific to a given project (see discussion above). DOC’s PEA does note that under NEPA EJ concerns must consider adverse effects on “minority populations”, “low income populations”, and “Native American Tribes” (United States Department of Commerce and National Institute of Standards and Technology, 2023, page 69 see above the discussion of models of justice per Liboiron et al., 2023).

DOC’s PEA, however, is about any number of projects that might be considered for funding under the CHIPS program. Consequently, DOC’s PEA has little of substantive analysis of EJ concerns between claiming that proposed action, “could be both beneficial and adverse” (United States Department of Commerce and National Institute of Standards and Technology, 2023, p. 79).

Beneficial effects include increased employment in the short to medium term resulting from construction projects and long-term during the operational phase of new semiconductor facilities. Meanwhile, negative impacts are deemed to likely be negligible, temporary, and localized relating to noise pollution and air emissions.

Socioeconomic

Perhaps unsurprisingly, DOC argues that socioeconomic impacts from projects under the CHIPS act will only be positive (United States Department of Commerce and National Institute of Standards and Technology, 2023, page 74-75). DOC anticipates that there will be employment opportunities in traditional trades (e.g., electricians, pipefitters, HVAC) and in specialized semiconductor equipment installation and operation. Yet, at best, proposed action under the CHIPS program “would have direct, minor, short-term to long-term beneficial effects on socioeconomics due to the creation of specialized employment opportunities” while “indirect socioeconomic effects to downstream industries would be long-term, beneficial, and moderate” (United States Department of Commerce and National Institute of Standards and Technology, 2023, page 82, emphasis in the original). The rather muted character of anticipated socioeconomic affects is notable given the way boosters of CHIPS emphasize the potential employment effects of this industrial policy.

Conclusion

DOC’s environmental impact submission arrives at a finding of no significant impact (‘FONSI’) on each impact category it considers by relying on five types of justification:

1) Misleading comparisons and false equivalencies. For example, DOC compares emissions from individual semiconductor facilities to emissions from the entire semiconductor sector and to the US as a whole. Such comparisons make the emissions from an individual facility appear insignificant.

2) Recognition and dismissal of known effects. For example, DOC’s assessment recognizes even with improvements in efficiency and waste management, increase semiconductor manufacturing will result in increases in pollution and waste (e.g. emissions; aka the rebound effect or Jevons paradox). While recognized, these effects are simply waved away with a faith in solutionism (see below).

3) Scalar mismatch, which refers to a misalignment between identified problems and solutions. A good example of this appears in the DOC’s discussion of chemical pollution from the semiconductor industry, particularly per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS). DOC’s assessment relies on a threshold here theory of harm, yet some PFASs can cause harm on contact rather than after exceeding some lower limit.

4) Faith in regulatory capacity and enforcement. The application of environmental and occupational health and safety regulations have been under chronic attack for at least 40 years (Oreskes and Conway, 2023), but that attack has intensified since the US Supreme Court overturned Chevron (United States Supreme Court, 2024; United States Supreme Court, 1984).

5) Faith in technological solutionism (e.g., treatment of hazardous materials and waste; water recycling efficiency) or, “a theory of change that posits that a social problem can be ‘solved’ deterministically by a technological design.” (Angel and Boyd, 2024, p. 88; see also, Morozov, 2013).

Will these five types of justification hold up in the analyses of NEPA submissions from individual semiconductor companies like TSMC, Intel, and Micron? Subsequent post(s) will dig into this question as well as what these publicly available documents might be able to demonstrate about the geographies of environmental impacts of semiconductor manufacturing.

Works Cited

Angel, María P., and Danah Boyd. 2024. “Techno-Legal Solutionism: Regulating Children’s Online Safety in the United States.” In Proceedings of the Symposium on Computer Science and Law, 86–97. Boston MA USA: ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/3614407.3643705.

Arizona Department of Water Resources. n.d. “Drought Frequently Asked Questions | Arizona Department of Water Resources.” Accessed June 20, 2023. https://new.azwater.gov/drought/faq#:~:text=A%3A%20Arizona%20has%20been%20in,according%20to%20statewide%20precipitation%20patterns.&text=Unlike%20hurricanes%20and%20tornadoes%2C%20drought,and%20long%2Dterm%20drought%20conditions.

Bernstein, Alan, Bob DeGrasse, Rachel Grossman, Chris Paine, and Lenny Siegel. 1977. “Silicon Valley: Paradise Or Paradox?: The Impact of High Technology Industry on Santa Clara County.” Pacific Studies Center.

Blum, Arlene, Simona A. Balan, Martin Scheringer, Xenia Trier, Gretta Goldenman, Ian T. Cousins, Miriam Diamond, et al. 2015. “The Madrid Statement on Poly- and Perfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs).” Environmental Health Perspectives 123 (5): A107–11. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1509934.

Boudia, Soraya, and Nathalie Jas, eds. 2014. Powerless Science? Science and Politics in a Toxic World. The Environment in History: International Perspectives, volume 2. New York: Berghahn Books.

Bowker, Geoffrey C., and Susan Leigh-Star. 1999. Sorting Things Out: Classification and Its Consequences. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

Bowman, Jessica. 2015. “Response to “Comment on ‘Fluorotechnology Is Critical to Modern Life: The FluoroCouncil Counterpoint.” Environmental Health Perspectives 123 (7): A170–71. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1510207.

Bowman, Jessica S. 2015. “Fluorotechnology Is Critical to Modern Life: The FluoroCouncil Counterpoint to the Madrid Statement.” Environmental Health Perspectives 123 (5): A112–13. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1509910.

Cousins, Ian T., Simona A. Balan, Martin Scheringer, Roland Weber, Zhanyun Wang, Arlene Blum, Miriam Diamond, et al. 2015. “Comment on ‘Fluorotechnology Is Critical to Modern Life: The FluoroCouncil Counterpoint to the Madrid Statement.’” Environmental Health Perspectives 123 (7): A170–A170. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1510207.

DeWitt, Jamie C., ed. 2015. Toxicological Effects of Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances. Molecular and Integrative Toxicology. Cham: Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-15518-0.

DeWitt, Jamie C., Juliane Glüge, Ian T. Cousins, Gretta Goldenman, Dorte Herzke, Rainer Lohmann, Mark Miller, et al. 2024. “Zürich II Statement on Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs): Scientific and Regulatory Needs.” Environmental Science & Technology Letters 11 (8): 786–97. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.estlett.4c00147.

Foucault, Michel. 1982. “Is It Really Important to Think? An Interview Translated by Thomas Keenan.” Philosophy & Social Criticism 9 (1): 30–40. https://doi.org/10.1177/019145378200900102.

Johnson, Dexter. 2022. “Scarcity Drives Fabs to Wastewater Recycling – IEEE Spectrum.” January 25, 2022. https://spectrum.ieee.org/fabs-cut-back-water-use.

Jones, Emily Tyrwhitt and RINA Tech UK Limited (RINA). 2023. “The Impact of a Potential PFAS Restriction on the Semiconductor Sector.” 2022-0737 Rev. 0. SIA PFAS Consortium.

Klaunig, James E., Motoki Shinohara, Hiroyuki Iwai, Christopher P. Chengelis, Jeannie B. Kirkpatrick, Zemin Wang, and Richard H. Bruner. 2015. “Evaluation of the Chronic Toxicity and Carcinogenicity of Perfluorohexanoic Acid (PFHxA) in Sprague-Dawley Rats.” Toxicologic Pathology 43 (2): 209–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192623314530532.

Lay, Dean, Ian Keyte, Scott Tiscione, and Julius Kreissig. n.d. “Check Your Tech: A Guide to PFAS in Electronics.” ChemSec. Accessed October 4, 2023. https://chemsec.org/app/uploads/2023/04/Check-your-Tech_230420.pdf.

Liboiron, Max. 2021. Pollution Is Colonialism. Duke University Press.

Liboiron, Max, and Josh Lepawsky. 2022. Discard Studies: Wasting, Systems, and Power. Massachusetts: MIT Press.

Liboiron, Max, Rui Liu, Elise Earles, and Imari Walker-Franklin. 2023. “Models of Justice Evoked in Published Scientific Studies of Plastic Pollution.” FACETS 8 (January):1–34. https://doi.org/10.1139/facets-2022-0108.

Ling, A.L. 2024. “Estimated Scale of Costs to Remove PFAS from the Environment at Current Emission Rates.” Science of the Total Environment 918. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.170647.

Mol, Annemarie. 2002. The Body Multiple: Ontology in Medical Practice. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press.

Morozov, Evgeny. 2013. To Save Everything, Click Here: The Folly of Technological Solutionism. New York: PublicAffairs.

Murphy, Michelle. 2006. Sick Building Syndrome and the Problem of Uncertainty | Environmental Politics, Technoscience, and Women Workers. Durham: Duke University Press.

O’Brien, Mary H. 1993. “Being a Scientist Means Taking Sides.” BioScience 43 (10): 706–8. https://doi.org/10.2307/1312342.

O’Laughlin, Logan Natalie. 2020. “Troubling Figures: Endocrine Disruptors, Intersex Frogs, and the Logics of Environmental Science.” Catalyst: Feminism, Theory, Technoscience 6 (1). https://doi.org/10.28968/cftt.v6i1.32350.

Oreskes, Naomi, and Erik M. Conway. 2010. Merchants of Doubt: How a Handful of Scientists Obscured the Truth on Issues from Tobacco Smoke to Global Warming. London: Bloomsbury.

———. 2023. The Big Myth: How American Business Taught Us to Loathe Government and Love the Free Market. Bloomsbury Publishing USA.

Perkins, Tom. 2024. “Industry Acts to Head off Regulation on PFAS Pollution from Semiconductors.” The Guardian, August 24, 2024, sec. Environment. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/article/2024/aug/24/pfas-toxic-waste-pollution-regulation-lobbying.

Peters, Jeffrey M., and Frank J. Gonzalez. 2011. “Why Toxic Equivalency Factors Are Not Suitable for Perfluoroalkyl Chemicals.” Chemical Research in Toxicology 24 (10): 1601–9. https://doi.org/10.1021/tx200316x.

Rekdal, Ole Bjørn. 2014. “Academic Urban Legends.” Social Studies of Science, June, 0306312714535679. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306312714535679.

Ritscher, Amélie, Zhanyun Wang, Martin Scheringer, Justin M. Boucher, Lutz Ahrens, Urs Berger, Sylvain Bintein, et al. 2018. “Zürich Statement on Future Actions on Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs).” Environmental Health Perspectives 126 (8): 084502. https://doi.org/10.1289/EHP4158.

Scheringer, Martin, Xenia Trier, Ian T. Cousins, Pim De Voogt, Tony Fletcher, Zhanyun Wang, and Thomas F. Webster. 2014. “Helsingør Statement on Poly- and Perfluorinated Alkyl Substances (PFASs).” Chemosphere 114 (November):337–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2014.05.044.

Semiconductor PFAS Consortium Plasma Etch and Deposition Working Group. 2023. “PFAS-Containing Fluorochemicals Used in Semiconductor Manufacturing Plasma-Enabled Etch and Deposition.” https://www.semiconductors.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/FINAL-Plasma-Etch-and-Deposition-White-Paper.pdf.

Semiconductor PFAS Consortium Wet Chemicals Working Group. 2023. “PFAS-Containing Wet Chemistries Used in Semiconductor Manufacturing.” Semiconductor Industry Association (SIA). https://www.semiconductors.org/pfas/.

Stevens, J. 1988. Robertson, Chief of the Forest Service, et al. v. Methow Valley Citizens Council et al. United States Supreme Court.

United States Bureau of Labor Statistics. 2009. “After the Dot-Com Bubble: Silicon Valley High-Tech Employment and Wages in 2001 and 2008.” https://www.bls.gov/opub/btn/archive/after-the-dot-com-bubble-silicon-valley-high-tech-employment-and-wages-in-2001-and-2008.pdf.

United States Department of Commerce and National Institute of Standards and Technology. 2023. “Draft Programmatic Environmental Assessment for Modernization and Internal Expansion of Existing Semiconductor Fabrication Facilities under the CHIPS Incentives Program.” CHIPS Program Office. https://www.nist.gov/document/chips-modernization-draft-pea.

United States Environmental Protection Agency. 2022. “Electrical & Electronic Components (40 CFR Part 469) Detailed Study Report.” EPA-821-R-22-005. Washington, D.C. https://www.epa.gov/system/files/documents/2023-01/11197_EEC%20Study%20Report_508.pdf.

United States National Archives. 1970. English: President Richard Nixon Signing the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969, 1/1/1970. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/27580121. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:President_Richard_Nixon_Signing_the_National_Environmental_Policy_Act_of_1969.jpg.

United States Supreme Court. 1984. Chevron U.S.A., Inc. v. NRDC, 467 U.S. 837 (1984).

———. 2024. Loper Bright Enterprises et al v. Raimondo, Secretary of Commerce, et al.

Venturini, Tommaso. 2010. “Diving in Magma: How to Explore Controversies with Actor-Network Theory.” Public Understanding of Science 19 (3): 258–73. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963662509102694.

Venturini, Tommaso, and Anders Kristian Munk. 2021. Controversy Mapping: A Field Guide. Wiley.

Wynne, Brian. 1987. Risk Management and Hazardous Waste: Implementation and the Dialectics of Credibility. Springer London, Limited.

———. 1994. “Scientific Knowledge and the Global Environment.” In Social Theory and the Global Environment, edited by Michael Redclift and Ted Benton, 169–89. London: Routledge.

Yates, JoAnne, and Craig N. Murphy. 2019. Engineering Rules: Global Standard Setting since 1880. 1st, Johns Hopkins paperback edition ed. Hagley Library Studies in Business, Technology, and Politics. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

You must be logged in to post a comment.