Discard studies offers an important concept for tech criticism: defamiliarization. The concept comes from the worlds of art and theatre and basically refers to some sort of device that helps make the familiar or taken for granted seem strange once again. The point of defamiliarization is to highlight how the way things are is not how they must be. Such a device–maybe a turn of phrase or a seemingly peculiar set design–enables an audience to ask questions: Must things be this way? Says who? For whom, where, when, and under what conditions?

In discard studies the defamiliarization argument starts from the observation that people often mistake the waste that they deal with personally as what waste is in general. That mistake can happen because waste is so mundane and yet so visceral. People deal with it every day and it is often associated with unpleasantness at best – – it is stinky, slimy, or just plain gross–so someone dealing with that kind of personal waste may have a gut feeling that, ‘Yup. I know waste’. Yet that familiarity can get in the way of analysis because it mistakes specifics for generalities. Most pollution and waste arise upstream in mining for, and manufacturing of, commodities. With respect to digital devices – – admittedly, a loose category – –the situation looks like this:

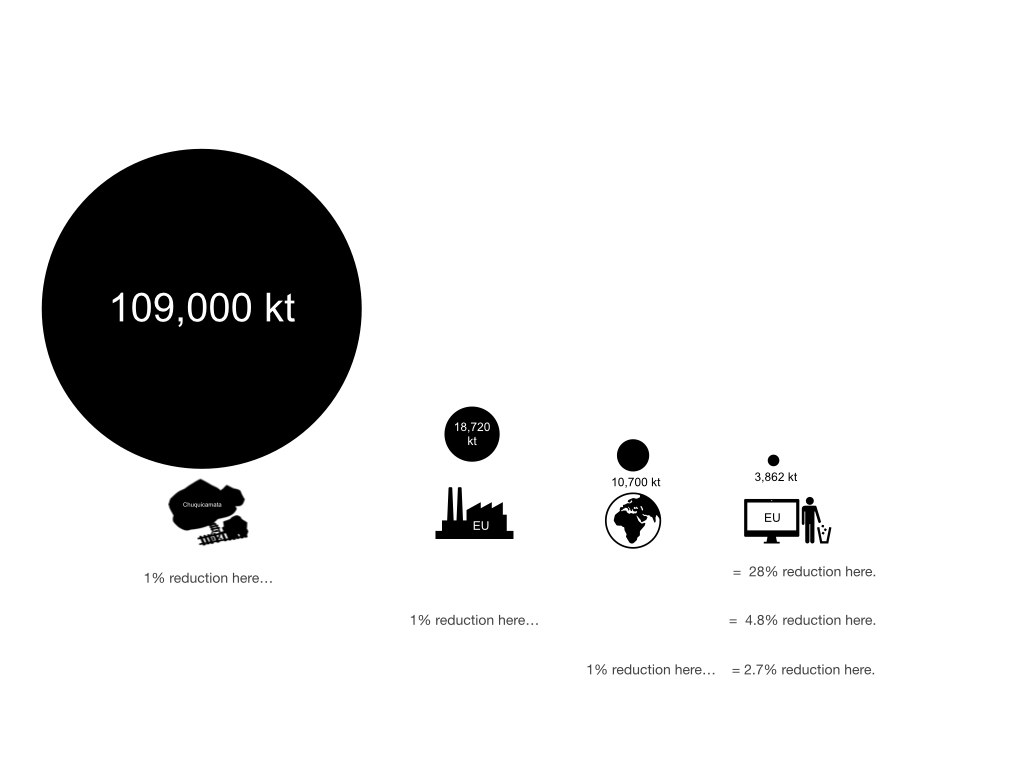

Figure 1. Usually when electronic waste (or ‘e-waste) is discussed, the story defaults to a post-consumer view of the problem: e-waste is what happens when people (consumers) throwaway their devices. This image shows the mass of waste arising from the mining for and manufacturing of electronics as well as what crosses-borders globally relative to post-consumer discards.

Data from: https://www.europenowjournal.org/2019/05/06/europe-has-e-waste-problems-exporting-to-africa-isnt-one-of-them/

Data for global transboundary flows are for year 2020 found on p. 5 of: Basel Secretariat. “Proposal by Ghana and Switzerland to Amend Annexes II, VIII and IX to the Basel Convention on the Control of Transboundary Movements of Hazardous Wastes and Their Disposal,” January 19, 2021. https://resource-recycling.com/resourcerecycling/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/UNEP-CHW-COMM-COP.15-Amendement-AnnexII-VIII-IX-20210119.English-1.pdf.

Something similar to mistaking personal or household waste as waste in general goes on, I think, in a lot of ‘tech criticism’ that mistakes user experiences for ‘Technology’ (capital ‘T’). It is important to examine the implications of that conflation because it risks automatically bracketing out huge portions of the lives of electronics from critical analysis. Similar to how waste that a person or a household puts in a trashcan or a recycling bin doesn’t account for total waste arising, critique that starts and ends with user experiences risks being unaccountable to the fuller gamut of people, places, and things that constitute digital technologies. It also risks the drawbacks of consumer/user awareness campaigns where there is an assumption that changing peoples’ awareness will automatically change their behavior. Discard studies shows that this is a questionable assumption as well.

An overly tight analytical bracket around user experiences is software-centric. Software-centricity has a tendency to take hardware for granted. Even in critical studies of sites like data centers, where physical infrastructure is often an important part of the critical analysis, the focus is often on servers-in-use. So, studies are published that critically examine the energy and water requirements to run and to cool servers and data centres. I’m not suggesting such studies are ‘wrong’ but they do seem to take hardware for granted. Hardware, on the other hand, enters these frames of analysis as a kind of unspoken, taken-for-granted substrate that is simply ‘there’ and left unexamined too often in my view. Yet hardware manufacturing has hugely consequential ecological impacts—and is itself impacted by ecological conditions.

If I have this notion of software centricity right–and maybe I don’t–then I have a purely speculative hunch about the persistence of software centricity in critical tech analysis. Scholars in discard studies and waste studies, particularly historians, have dug deep into the evidence of how industry responded to mid-20th Century murmurings of certain forms of environmentalism, such as concerns about litter and recycling. One industry strategy was to fund public relations and educational campaigns directed at individual responsibility for litter and recycling issues. Those campaigns kept the public and regulatory gazes off of the industries who produced the things and/or the packaging they came in and, thus, diverted responsibility away from those companies bottom lines. These kinds of campaigns are ongoing, but the legacies of earlier rounds of them are very much with us. Who in the face of this or that environmental dilemma – – disposable packaging, single use plastics, or the uber-crisis of climate–has not asked, ‘What can I do?’ The question posed in such a frame assumes that what matters is my individual action aggregated up by the millions of others into a solution to this or that dilemma. Discard studies describes the latter as a scalar mismatch – – I misalignment between the action proposed as a solution and the magnitude of the problem and its concrete power differentials. My purely speculative hunch is that software centricity comes from a similar place or takes on board without noticing the legacies of this kind of individualist/individualized solutionism. It does so because user experiences are mistaken for ‘tech’. Yet, a risk of such software-centricity is mistaking individualized actions–abstain from Netflix, decouple from Google–as actions that can and will automatically aggregate up: worry about the carbon footprint of your online searches, your online streaming, or your use of cloud services. But, like with litter and recycling, all that attention on individualized action keeps citizen and regulatory attention off of the industrial mining for, and manufacturing of digital technologies and the hardware of which they are composed and on which software runs.

Look back at Figure 1. No amount of individualized action around recycling devices that you may discard is going to touch the pollution and waste arising in the mining for, or the manufacturing of, hardware. Moreover, organizing the action that would reduce the pollution and waste arising even at a single mine site or in manufacturing is going to be very different than the individual action of, say, repairing a device you already have. An overly tight focus on user experiences, or what I’m calling software centricity, risks a misalignment between problems identified and actions for change proposed.

You must be logged in to post a comment.